Connecting flights are almost as old as commercial aviation itself. Starting from 1947, when IATA introduced the concept, airlines began teaming up to expand their networks and provide passengers with better service. Over the last few decades, the system noticeably transformed to fit the changing market, yet not nearly enough to leave every party satisfied.

We're going to review the current state of the interline framework, address pressing challenges, and discuss how the industry is working towards eliminating them. But first, let’s get an understanding of how different types of collaboration between airlines work.

What is interlining?

Interlining, the earliest form of connecting flights, is still in use today. It allows travelers to book tickets that combine flights from two or more different airlines into a single itinerary.

Although the journey consists of several flight legs, a customer only needs to check in once, with their bags automatically transferred during the layover. In case of disruptions, they will be safely rebooked to another flight. At the same time, passengers are informed from the start which airline is responsible for each part of the trip.

At the same time, with interlining, airlines can access more markets without actually expanding their operations, sell more tickets, and become more attractive to passengers due to the availability of more itineraries.

“Interline agreements basically are one way of improving your revenues because you actually can book customers on routes that you do not operate on,” shares Sekhar Mallipeddi, travel and hospitality advisor with decades-long experience in aviation. “And then the technologies definitely help because most of the PSS systems that airlines use support interlining out of the box. Most of the GDSs absolutely support interlining out of the box as standards.”

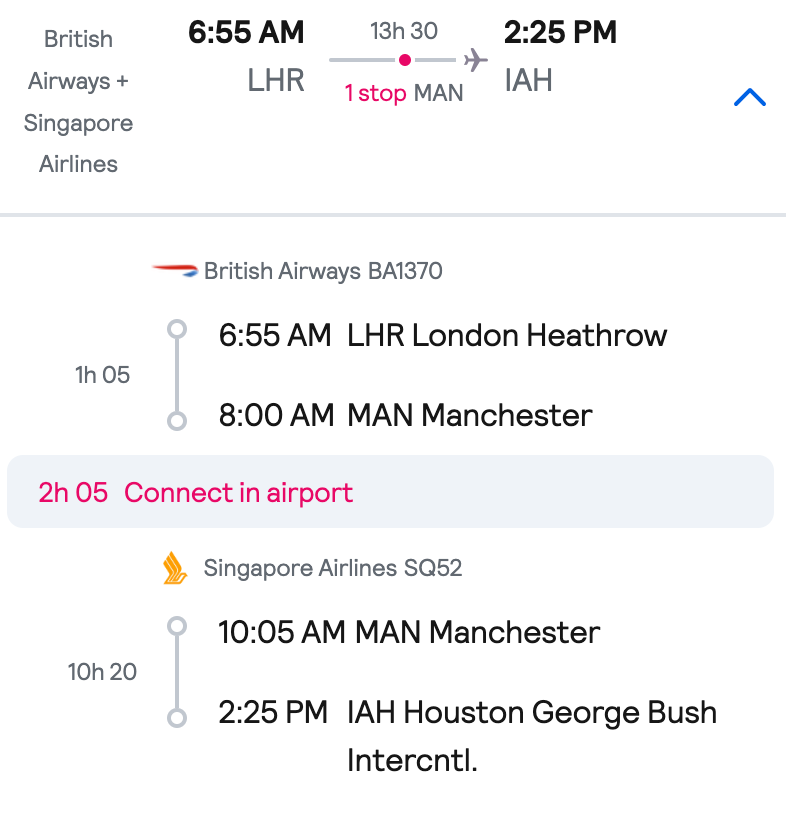

An interline ticket available through a partnership between BA and Singapore Airlines. Source: Skyscanner

How interlining works

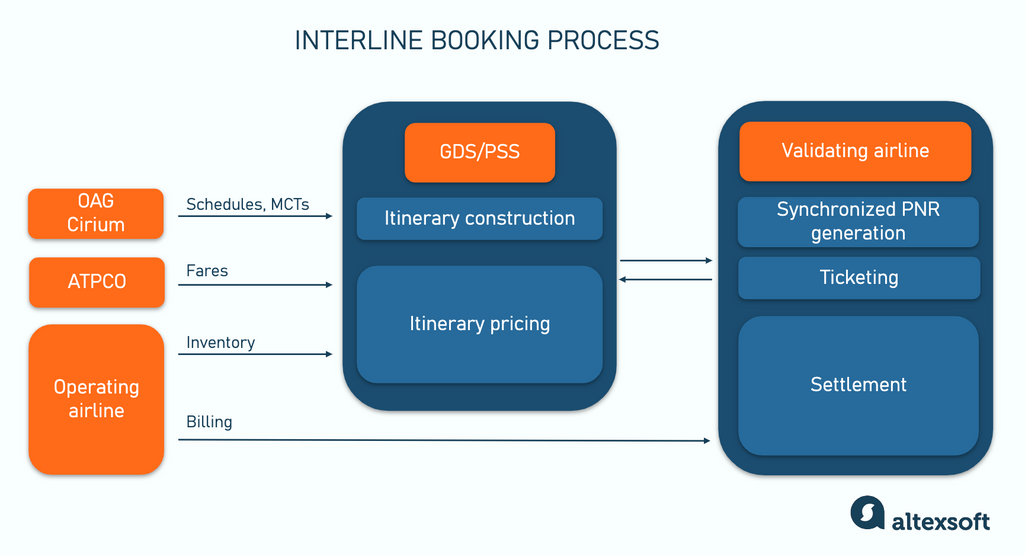

The airline that sells the interline ticket is called the validating carrier and their partner conducting one or more legs of the trip is an operating carrier. Internally, the interline booking flow looks like this.

How interline booking works

Itinerary Construction. Upon request from a passenger or travel agent, a Global Distribution System (an intermediary that facilitates indirect reservations) or a Passenger Service System (software used by airlines) creates an itinerary. If no direct flights are available, it assembles options with complex routes using interline agreements, published schedules, and minimum connecting times (MCTs). This data comes from data aggregators like OAG or Cirium or directly from airline reservation systems.

Itinerary Pricing. A GDS (in case of indirect channels) or a PSS (for direct distribution) compiles availability information from each airline involved in the journey and retrieves published fares from ATPCO (Airline Tariff Publishing Company) to price the multi-leg trip.

Synchronized PNR Generation. The pricing and itinerary data are sent to a validating airline, which links all segments into a synchronized PNR. A PNR (Passenger Name Record) is a digital document containing itinerary details and a synchronized PNR does the same for multi-leg trips.

Ticketing. Upon payment, the validating airline issues a single ticket covering all legs of the journey.

Settlement. After the journey begins, operating airlines bill the validating airline for their portion of the fare. Billing and settlement are processed through the IATA Clearing House (ICH).

Interline agreements

The original interline framework was established by IATA in the early days of commercial aviation. At that time, all airlines in the US charged pretty much the same fees, as set by the government, so the rules of their collaboration were standard for all and didn’t take into account the commercial objectives of each carrier. To interline, carriers had to join the Multilateral Interline Traffic Agreement (MITA), which provided standards for cooperation between airlines.

But the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978 changed the industry forever. It finally allowed carriers to set prices independent of the government, creating greater complexity. So, to work together, airlines now required more contracts. This is why today, in addition to MITA, partners typically sign IATA’s Multilateral Prorate Agreements (MPAs) or Special Prorate Agreements (SPA) to decide how revenue from tickets is split between them. Other bilateral contracts establish responsibilities and clarify policies for baggage handling, rebooking, schedule changes, and more.

MITA is still a standard way to enter interline agreements, but the need for more control over revenue and flight offerings led to the desire for closer cooperation. Which is why today a different model – codesharing – is widespread.

What is a codeshare flight?

Popularized by Qantas and American Airlines, codeshare was meant to offer a closer partnership between carriers. Now, it has become just as popular as interlining, if not more.

The main idea of a codeshare is in its name. Here, an airline can sell its partners' flights as its own flights, under its own code. In this case, the airline selling the multi-leg itinerary is called a marketing carrier.

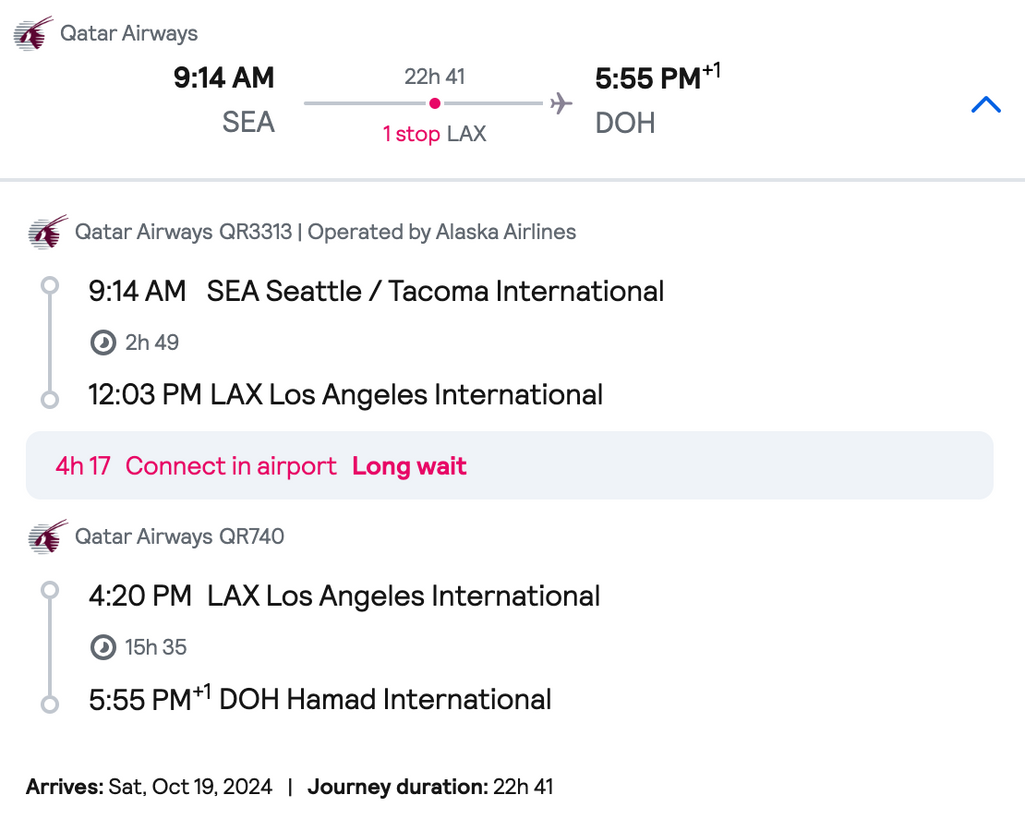

If the flight has a note “operated by X airline”, it’s a telltale sign of a codeshare agreement. Source: Skyscanner

For example, if Qatar Airways sells a flight from Seattle to Doha with a layover in Los Angeles, it can market the whole trip as a Qatar flight, even though the first half of it is operated by its codeshare partner – Alaska Airlines.

If they don’t pay too much attention, the passenger's experience will remain relatively the same as with interline flights. Yes, they may scratch their head when boarding the aircraft marked by a different carrier, but the convenience will remain. One of the benefits unavailable through usual interlining would be that the passenger can enjoy the privileges of loyalty program membership and accrue frequent flyer miles of the marketing airline.

How codeshares work

In codeshare agreements, the marketing airline files and markets the operating airline's schedules as their own, making it appear that they operate the flight.

It can manage the operating airline's inventory in three main ways.

- Block space – the marketing airline buys a specific number of seats in advance, keeping them separate from the operating airline's inventory and deciding which booking classes the seats are sold in on its own.

- Free flow – both airlines exchange seat availability information in real time, with no specific seats allocated exclusively.

- Capped free flow – the marketing airline has a maximum seat allocation, which cannot be exceeded.

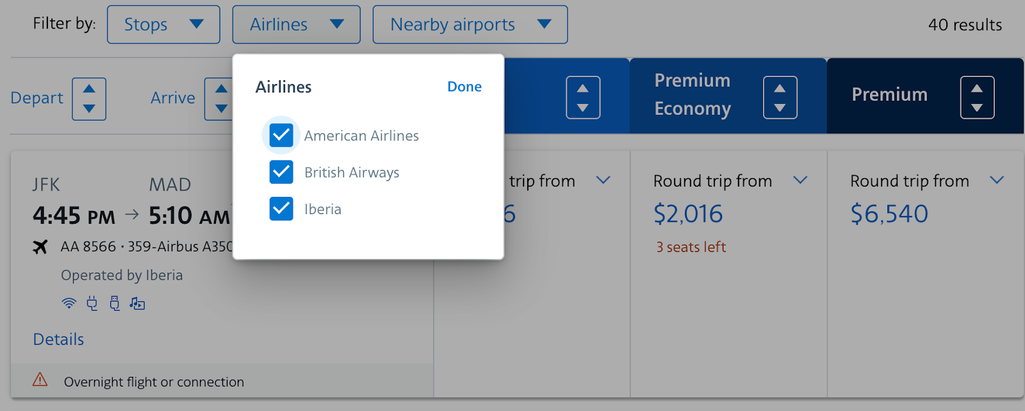

The AA website even allows you to choose which partner to display for its Madrid flights. Source: American Airlines

However, codeshare agreements are costly, complex, and resource-intensive, with higher chances of system failures.

“The problem with codeshare is that you need synchronization. So when something happens to the codeshare flight, you need those synchronization messages to go from system to system and that is not cheap. And you need these flights to act like they're your flights. Here, integration and testing is much more difficult. With an interline, you really don't need that kind of testing. You just need to sell the other flight.”

Airline alliances and joint ventures

The popularity of codeshare agreements led to the development of the world’s biggest airline alliances. Star Alliance, Skyteam, and Oneworld are organizations whose members work together by sharing resources, like IT infrastructure, ground handling personnel, and even investments. Typically, members of the same alliance are in codeshare agreements with each other. And there’s evidence that the more codeshare partners a carrier has, the larger its margins are, especially among members of the same alliance.

And while we’re at it, there's an even higher level of collaboration called joint ventures. In a rare case, a small number of airlines will agree to operate as a single business on specific routes or markets. For example, Delta, Virgin Atlantic, and Air France-KLM are in a transatlantic joint venture, while Qantas has a joint venture with Emirates on European flights. This type of cooperation doesn’t really fall under the interlining classification, so we won’t be touching on it further.

Challenges in modern interlining and codesharing

The interline and codesharing network has been a cornerstone of the aviation industry for decades, serving travelers and generating revenues for carriers. However, in a world where we still experience the devastating impact of the pandemic as well as supply chain and capacity issues, some problems that exist in the current state of affairs have become more apparent.

Legacy technology

Aviation still majorly relies on frameworks and systems, groundwork that was laid out decades ago. If you want to enter the interline world and cooperate in the sphere, you’ll need to play by their obsolete rules. New entrants struggle with the massive amounts of agreements, standards, and legacy technologies they must support.

So it's no surprise that low-cost carriers rarely if ever enter partnerships with other carriers due to this complexity.

“So imagine you're Ryanair and you're really cheap and you're efficient, you're extremely, extremely agile, and then you start to interline with British Airways or Iberia or somebody that tends to be less efficient. It doesn't mix, right? So the reason why they are low cost is because they're highly efficient.”

High entry cost

Entering interline and codeshare agreements is also a costly and complex affair involving many operational and legal investments. Airlines must not only join MITA and the IATA clearing house, which will set them back hundreds of thousands of dollars, but also pay separate fees to a GDS, PSS provider, and other players involved. For example, by IATA standards, an operating airline pays 9 percent of its share of the fare to a validating airline to compensate for ticketing and reservation services.

You can read the full breakdown of related expenses in our article on virtual interlining, but you get the picture.

Poor implementation of NDC

NDC or New Distribution Capability is the XML-based communication standard introduced by IATA in 2012. Its aim was to fix the retailing problem with legacy distribution, which doesn’t allow carriers to sell all ancillary services and personalized offers via third parties. Nor did it support rich content like photos, videos, and text descriptions.

Over the past years, many airlines adopted NDC as part of their PSS, via a third-party solution or by building a custom NDC layer.

And it works well with codesharing. “You can sell codeshare in the NDC environment,” says Ann Cederhall. “That's no problem, because you can sell anything with your own flight numbers on it. It becomes a bit problematic in the NDC channel if you have irregular operations. Let's say you have a flight that's canceled and you need that to be rebooked on another airline. Then that other airline is typically gone from your NDC channel unless you develop functionality to show the agent what the customer has been rebooked on."

But with traditional interlining, the support for NDC capabilities is very limited.

You still rely on MITA and EDIFACT systems. NDC does not fully support complex interline flow, so most interactions are processed through legacy EDIFACT-based systems. For example, to do interlining, airlines still need to file fares to the Airline Tariff Publishing Company (ATPCO).

“If you're truly doing NDC interlining, you should have other mechanisms to do pricing, shopping, where you do share those offers between the airlines and not use a traditional fare filing. You have to create shopping services that are above and beyond what exists today. You have to share fares,” discloses Mallipeddi. “So you can say interlining in NDC, but as of now, the implementations are still traditionally farefiled and shopped and ticketed.”

You might still have commercial restrictions. Many airlines use passenger service systems by companies that own GDSs which can impose commercial restrictions on what a carrier can sell over rival channels — NDC, non-NDC bilateral connections, or the airline’s website. Airlines like United that run their own PSSs can fully control their distribution, using all perks of NDC to deliver interline offers.

As of mid-2024, only 11 airlines have established interlining with one or few closest partners in the NDC channel (much more have implemented it in the codeshare scenario).

So, how do we fix this? As often happens, when the industry has gaps that don’t satisfy its players, a few different solutions arise. Let’s talk about them.

Alternatives to traditional interlining: virtual and managed interlining

IATA-driven interlining is, of course, not the only way for passengers to catch a connecting flight. Often, they create their own multi-leg itinerary when there’s no existing connection that fits their needs. But it can obviously be very risky – in case of delays, passengers must rebook their flight themselves. Plus, it can be quite an ordeal to manually search for the best combination of flights.

Virtual interlining

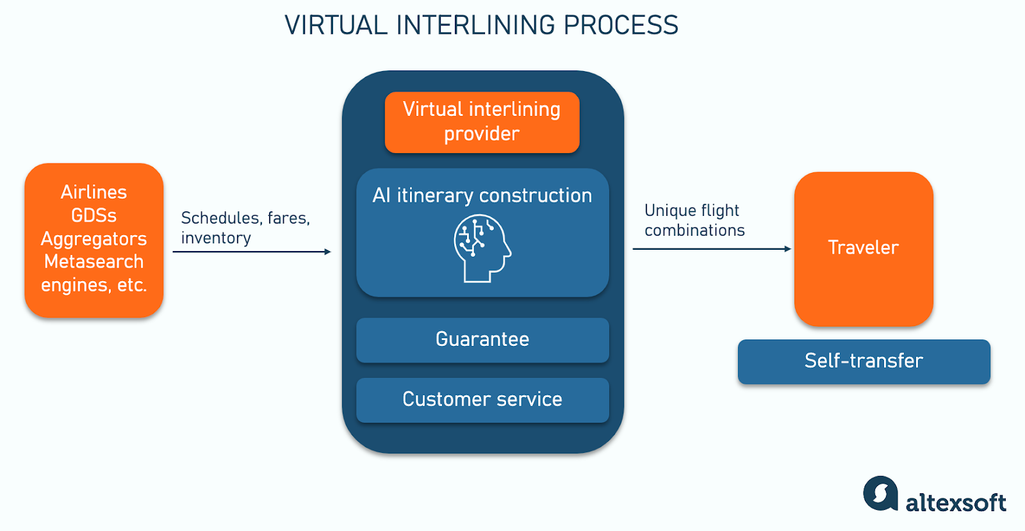

That’s why, in 2012, travel startup Kiwi.com introduced the model of virtual interlining. Here’s how it works.

The process behind virtual interlining

- Kiwi.com’s platform gathers data on schedules, fares, and availability from various airlines and other transportation providers (e.g., buses, trains) using API connections. This includes both traditional carriers and low-cost airlines that don’t typically partner with each other.

- Kiwi.com's AI algorithm identifies flight combinations across different airlines, creating possible itineraries that don’t traditionally connect. These itineraries span flights, buses, and trains to maximize travel options for customers.

- Once the traveler selects an itinerary, Kiwi.com processes the booking by reserving each segment independently. It handles ticketing, payments, and documentation for each leg of the trip, allowing customers to book all segments with one transaction, even though the journey involves multiple, non-partnered airlines.

- Kiwi.com often requires travelers to self-transfer between flights, meaning they must claim and recheck luggage where applicable.

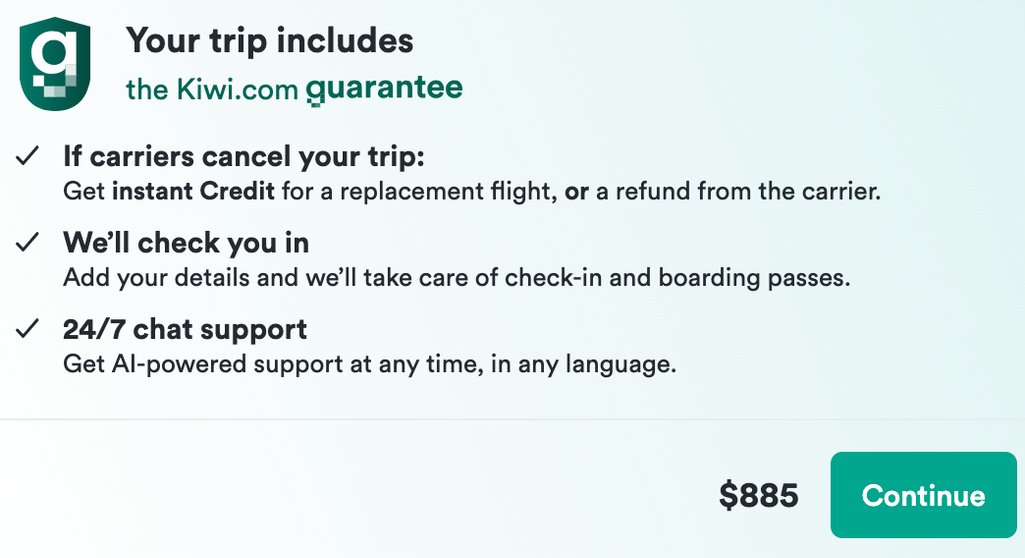

- If a delay on one segment causes the traveler to miss their next flight, Kiwi.com offers a unique guarantee, which includes rebooking assistance, alternative transportation, or even hotel accommodations if necessary. This guarantee aims to provide added security, covering travelers in the absence of formal interline agreements.

- Kiwi.com maintains dedicated customer service to assist with issues such as rebooking, lost connections, and last-minute changes, adding a level of reliability to the virtual interline experience.

Kiwi.com offers its guarantee service on most of the displayed flights. Source: Kiwi.com

Virtual interlining opens up more routes and can be cheaper than the traditional kind – after all, it can put you on a low-cost carrier, which mostly flies direct. But it doesn’t offer a comparable service. Participating airlines may not have any relationships, nor are they aware of this happening, so passengers will still have to check in their bags every time.

Managed interlining

This is where a more integrated model comes into play. It’s called managed interlining or enhanced virtual interlining.

Unlike Kiwi.com, which is a solution for travelers, managed interlining is facilitated by a B2B platform connected to airlines. This means that now, a third-party tech provider such as Dohop gathers data on schedules and availability from any airlines partnering with the platform and aggregates them into a central database. Then, just like Kiwi.com, the provider uses algorithms to match and combine flights from different airlines that might not otherwise connect.

In practice, this allows passengers to use, say, the Air France website to book connected journeys with the members of the same connectivity network, such as Transavia and SBB.

For carriers, this system allows interlining with a network of partners it wouldn’t be able to collaborate with otherwise, including ground transportation providers. The cost of the connectivity and the associated effort is also much lower than interline via IATA and the carriers aren’t responsible for managing baggage or delays. But the biggest benefit is that it gives carriers full control of retailing: The platform allows them to distribute under their own brand, sell ancillaries, and access customer data.

As of the time of writing, Dohop already partners with over 75 airlines like Alaska Airlines, Emirates, Spirit, alliances, and even rail providers.

Okay, so virtual and managed interlining is a solid method for interline between those carriers who normally don’t. But what do we do with carriers who already have interline or codeshare agreements? Is there a way to improve traditional interline?

Interline with Offers and Orders

In 2019, IATA proposed a new framework that would modernize traditional interlining.

It’s based on the Offer and Order management, a key concept introduced by the NDC standard to enable modern retailing in air travel. Instead of relying on predefined fare classes, this scenario allows airlines to generate a personalized travel package called an Offer, which becomes an Order when a customer accepts it. Carriers can catalog offers and control orders in the Offer & Order Management System (OMS).

For interline, this solves two problems:

- an Order contains information on the customer’s full itinerary, which can be accessed by any party at any touchpoint; and

- customers can be provided with richer and more contextual data.

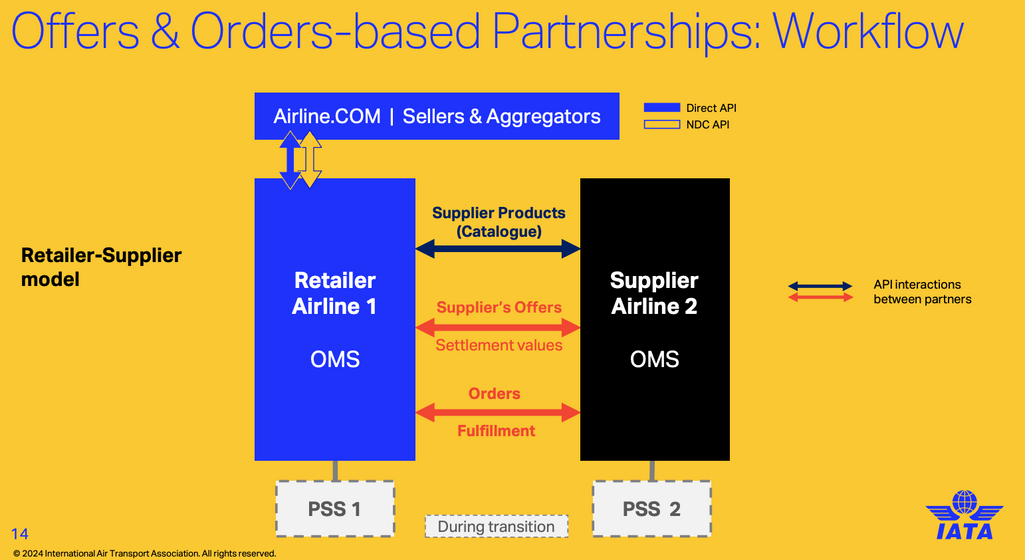

The new interline framework also adopts a new language when referring to partnering carriers. Here, a marketing or validating airline is called a Retailer and an operating carrier – a Supplier.

So how would the interline process work with this framework?

The visualization of partnerships based on Offers and Orders. Source: IATA

- The Retailer uses API connections to access schedules, fares, and availability from the Supplier’s OMS.

- The Supplier provides the requested catalog of products along with its Offers.

- When a traveler or travel agent selects an itinerary, the Retailer retrieves the necessary offers from the Supplier and then determines the final price to offer the customer.

- Once the traveler confirms their booking, the Retailer places an order through the system, which is then fulfilled by the Supplier. This involves processing ticketing, payments, and any necessary documentation for the entire interline journey.

- The Supplier sends settlement info to the Retailer to share revenues.

- Any disruptions, such as missed connections, are handled through real-time API interactions between the two airlines.

The new framework also introduces a new form of agreement. The Standard Retailer and Supplier Interline Agreement (SRSIA) that will exist alongside MITA will allow airlines to formalize all details in one document, including partnerships with LCCs and intermodal relationships. Parties won’t have to publish these agreements to IATA and will be in full control of constructing itineraries.

On top of that, the new framework will support existing standards of baggage movement, check-in, and immigration processes in airports. This topic is yet to be fully explored, but IATA promises that it will allow a seamless exchange of information, easing customers’ access to these services during interline journeys.

The new framework will also finally facilitate continuous pricing since a Supplier will remain in control of their offer when providing it to a Retailer. Being the most advanced form of dynamic pricing, continuous pricing allows airlines to expand the limit of 26 price points and provide prices that would suit each customer segment best.

As of now, carriers can already use SRSIA for their agreements and IATA’s pilots with British Airlines and Vueling. Singapore Airlines and Scoot have shown successful results. We’re positive that just like the development and adoption of NDC, the new interline framework will take shape over time.

Still, it doesn’t mean that it needs to be the only viable solution for the future of interline. There exists a different suggestion to modernizing interline.

Distributed ledger for interline payments

When airlines work together to provide interline flights, managing revenue, billing, and settlement among the participating carriers becomes very complex. This is due to the large number of factors involved, such as fare splits and baggage handling.

A few experts in the field have discussed one of the ways to improve it. Sekhar Mallipeddi, for instance, is a big proponent of applying distributed ledger technology.

A distributed ledger is a digital system with a decentralized design used for storing, recording, and maintaining transaction records and their details in numerous places simultaneously, guaranteeing their integrity and safety. And it can make interline processes more efficient by providing a shared, secure, and real-time system for managing these agreements. How exactly?

Real-time collaboration. A distributed ledger provides a shared, secure ledger with schedules and fares accessible to all interline partners, ensuring accuracy and reducing manual data errors. It also allows real-time response to disruptions, automatically logging events and triggering rebooking or accommodations.

Automated revenue sharing. Smart contracts enforce revenue-sharing rules automatically, calculating exact earnings for each airline and adjusting for additional fees.

Increased transparency and accountability. Distributed ledger's traceable record ensures accountability across transactions, helping airlines resolve disputes quickly with verified data.

Baggage tracking and handling integration. Distributed ledger enables unified, real-time baggage tracking, reducing instances of lost luggage and improving passenger experience.

Streamlined dispute resolution. Transparent records on a distributed ledger simplify and reduce disputes by providing a clear, accessible history of all transactions.

How do you implement a distributed ledger for interlining? There’s no ready-made solution. Sekhar Mallipeddi thinks that for this, “The ideal situation would be a small startup or a company that works with a governing body.”

“I think the right place to do it would be an existing organization,” Sekhar adds. “IATA or ATPCO are both very well positioned to do this. They tend to basically deal with highly standardized processes that exist that they implement.”

Since the adoption of this distributed ledger will depend on the number of carriers that are onboarded, it would be much harder for a private company to do this.

Maryna is a passionate writer with a talent for simplifying complex topics for readers of all backgrounds. With 7 years of experience writing about travel technology, she is well-versed in the field. Outside of her professional writing, she enjoys reading, video games, and fashion.

Want to write an article for our blog? Read our requirements and guidelines to become a contributor.