If you deal with international shipments, paperwork is an inevitable evil. It must be handled with care, since mistakes or inaccuracies can cause unwanted difficulties and lead to significant losses. In most cases, however, your freight won’t even be moved unless you have complete, proper documentation attached.

We’ve already talked about bills of lading, an essential document in ocean trade. Now, we look at air freight requirements and explore air waybills, i.e., how they work, what must be included, and how to digitize all this hassle.

What is an air waybill?

An air waybill or AWB (also called airway consignment note or dispatch note) is a legally binding transport document that accompanies goods shipped by an air carrier.

In layman's terms, an AWB is fairly similar to the Amazon shipping label you can find on any parcel you receive after your Black Friday (or, let’s be honest, tons of others) online purchases. Issued by an air carrier or carrier’s agent, an AWB provides all details about transported freight and enables tracking.

An AWB standard form was designed by the International Air Transport Association (IATA). IATA also provides instructions on how to correctly complete the AWB form within The Air Cargo Tariff and Rules (TACT) Solutions.

So first of all, let’s see what’s included in the AWB – and why.

AWB functions and information included

An AWB is the main document that regulates air shipping. To get a clear picture of what an AWB is and why it’s used, we have to fully understand its purpose and what information it contains. So, here’s a list of AWB functions in the air shipment process.

Contract of carriage – an agreement between a shipper and a carrier listing terms and conditions of goods transportation.

Evidence of receipt of goods by an airline – once signed, it’s a legal proof that an air carrier received the goods to be transported (in case any disputes arise).

Tracking of shipment – the AWB number is the essential information that enables cargo tracking. The route details and airport codes are also included.

Contact information among all parties – contact details of all the parties involved.

Freight bill – information about the charges involved in the shipment process so an AWB can serve as a bill or invoice together with supporting documents. It also supports the accounting process.

Customs declaration – it’s one of the essential documents required by customs authorities to allow freight transportation.

Description of the goods – the details on the number, weight, dimensions, value, and nature of goods being moved.

Guide for handling and delivering goods – special instructions on how to handle the shipment can be included, for example, for dangerous, fragile, or temperature-sensitive cargo.

Certificate of insurance – evidence that freight is insured containing details of insurance coverage.

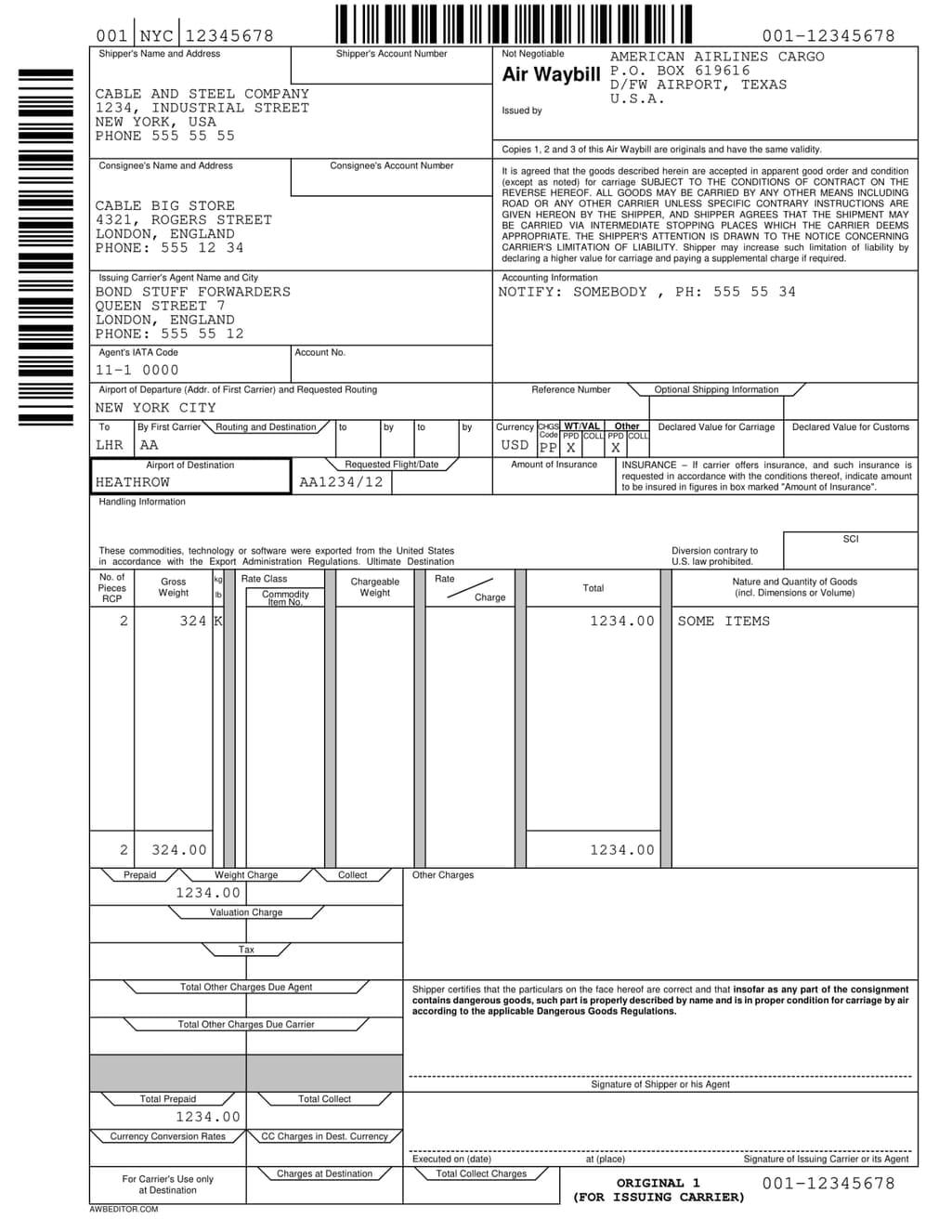

A sample AWB. Source: AWB Editor

The most essential and important information is listed on a single first page of the AWB. The reverse side of the air waybill looks like a usual contract and outlines the terms and conditions of the carrier (e.g., liability limits and claims procedures).

The AWB number is worth mentioning separately. It’s the 11-digit unique identification code usually located at the upper right corner and is used for tracking. The common pattern includes three parts: The first three digits are the airline prefix (the carrier’s ID number), the next seven digits are the AWB’s serial number, and the last digit is calculated by dividing the AWB serial number by seven (it’s called the check digit). There can be additional characters depending on the carrier.

A sample AWB number where 518 is the Canadian North airline code, 4102010 is the serial number, and 3 is the check digit

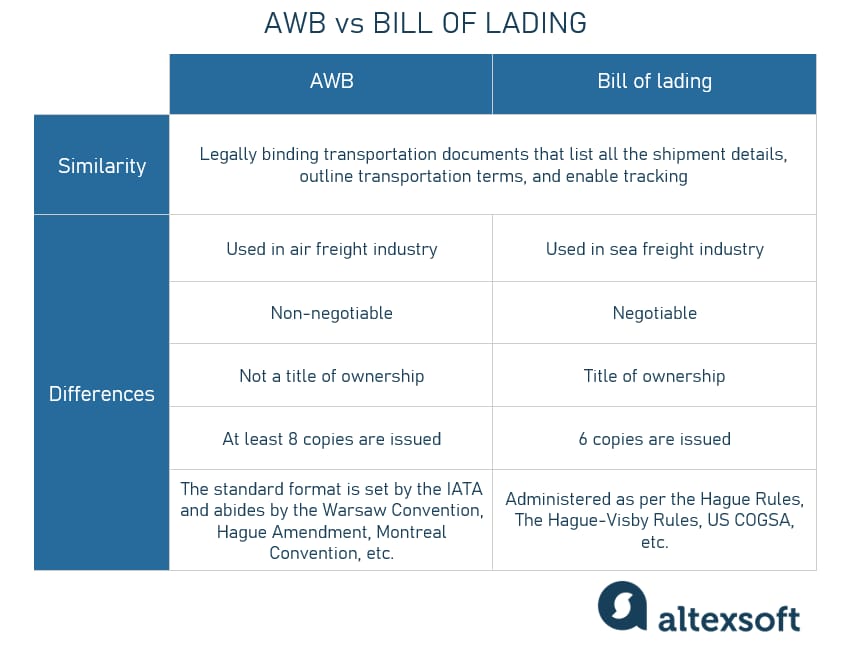

If you’re familiar with ocean shipment documentation, you might see that an AWB is very similar to a bill of lading (BOL), also a legally binding agreement about goods transportation. AWBs are even sometimes described as one of the BOL types. So, a natural question arising is how they are different.

AWB vs bill of lading

Well, as we said, the BOL is mainly used in the maritime and trucking industries, while AWBs regulate air cargo transportation. But the main difference between the two is that air waybills are non-negotiable documents (which, by the way, is clearly printed on top of each AWB), while bills of lading are usually negotiable. In a nutshell, it means that the right of ownership is not transferred with the AWB, unlike BOL.

AWBs basically only serve as receipts of goods and contracts for transportation, but a BOL can be a so-called document of title of goods or proof of ownership. That means that whoever has the duly endorsed BOL is in the rightful control and possession of goods.

AWB vs BOL

Types of AWBs: airline-specific AWB vs neutral AWB

As for the air waybill’s format, there are two types of AWBs, airline-specific and neutral.

Airline-specific AWBs include the air cargo carrier’s details, i.e., name, logo, as well as head office address and contact details. Such AWBs are issued on the specific carrier’s company form and must have the preprinted air waybill number. They also must be subject to IATA regulations and one of the international air conventions (Warsaw Convention, Hague amendment, Montreal Convention, etc.).

Neutral AWBs typically have a similar layout and format, but they don’t have the carrier’s information filled in. They’re also not required to follow IATA or air conventions rules.

Types of AWBs: Master AWB vs House AWB

Depending on who issues the AWB, two types of air waybills can be distinguished: House Air Waybill (HAWB) and Master Air Waybill (MAWB).

A House Air Waybill (HAWB) is issued by the freight forwarder to the sender of goods as a proof of receipt and shipping contract. Usually, it comes in a neutral AWB form, doesn’t contain any carrier’s information, and only regulates the relationships between the shipper and the forwarder. The HAWB number is issued by the forwarder and can’t be used for tracking on the carrier’s or third-party website.

A Master Air Waybill (MAWB) is issued by the carrier to the shipper or freight forwarder who acts on the shipper’s behalf. MAWBs are issued on the preprinted carrier form and contain prepopulated carrier identification details as well as the tracking number. MAWBs are what is usually referred to as AWBs since these are the documents that regulate the carrier’s responsibility to move freight.

Now, let’s briefly discuss the air freight transportation process and the AWB’s role in it.

AWB in the transportation process

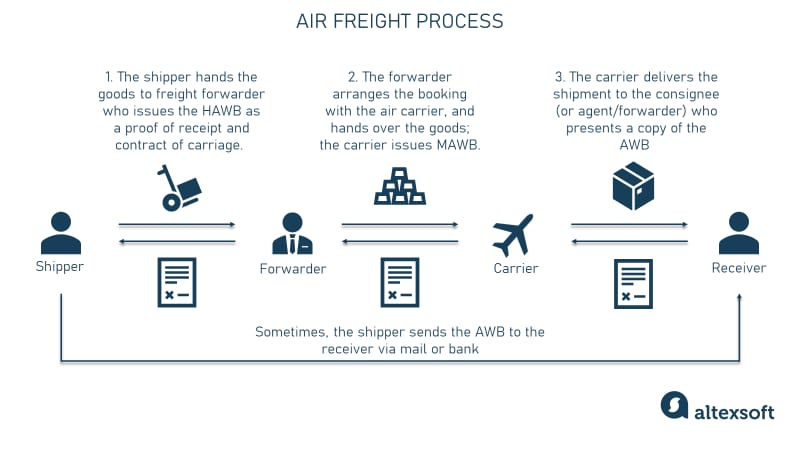

A very common scenario of the air freight shipping process involves four parties – the shipper, the freight forwarder (these guys only serve as intermediaries and are not an essential part of the chain), the carrier, and the recipient or consignee. Let’s look at how everything happens step by step.

The AWB in the air freight flow

- The shipper entrusts the freight forwarder to move goods, prepares the items to be shipped, and hands them over to the forwarder. The forwarder issues the HAWB as a proof of receipt and contract of carriage.

- The forwarder arranges the booking with the air carrier and hands over the goods, often consolidating with other cargo. Once all the export customs formalities are settled, the airline fills out the MAWB which, when signed by the carrier and the sender (freight forwarder in our case), becomes an enforceable contract with all the functions we listed above.

- Upon delivery, the shipment is handed over to the consignee (or agent/forwarder) who presents a copy of the AWB. The recipient receives a copy of AWB either from the sender (by mail/courier delivery or through the bank) or from the air carrier upon arrival at the destination. The AWB along with other documentation is necessary for import customs clearance and signifies the contract completion and cargo acceptance.

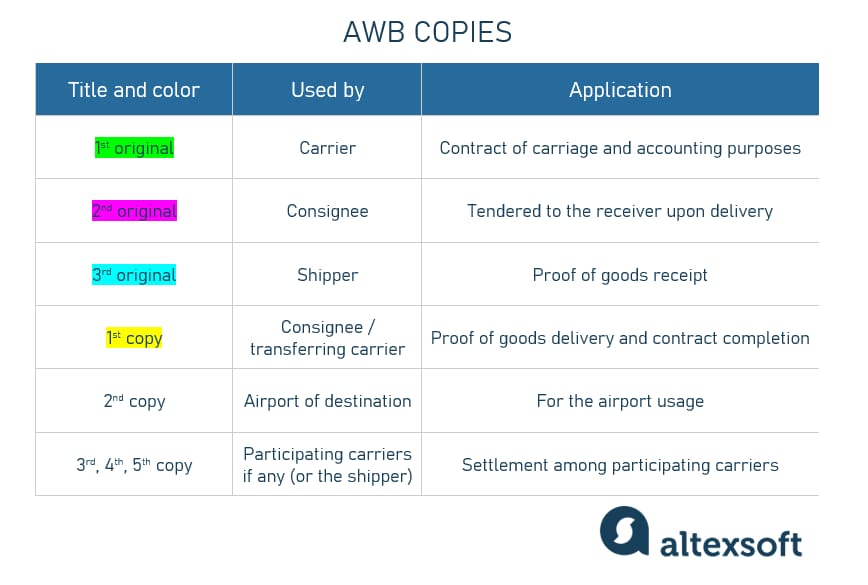

So, the AWB comes in 8 copies (or more) of different colors that are intended for each party involved.

AWB copies

AWB number for air waybill tracking

All the parties involved in the transportation process want to know where the shipment is. The AWB number allows all stakeholders to track the shipment status and check all the information related to the consignment.

Generally, air cargo carriers enable tracking via their own website for their clients’ convenience.

Tracking cargo with Air India

As an alternative, you can take advantage of third-party tracking information aggregators (e.g., track-trace or Ship24) to receive your shipment status details. It’s especially convenient when you need to track multiple shipments moved by different carriers. In most cases, you can access their functionality via their websites, while some providers allow users to integrate tracking into their own digital products (check track-traceConnect as an example).

In addition, some freight forwarders offer online tracking functionality for their clients via their freight management platforms.

The air freight volume keeps growing. In 2021, it exceeded 66 million metric tons. With every shipment requiring up to 30 types of documents with multiple copies, imagine how much paperwork it would demand – if not for adoption of e-AWBs.

Electronic air waybill (e-AWB) and how to implement it

Each shipment requires a bunch of accompanying documents that have to be stored, distributed, and kept track of. In 2010, IATA introduced an electronic air waybill (e-air waybill or e-AWB) that became the default contract of carriage for all air cargo shipments on January 1, 2019. It’s a part of IATA’s e-Freight program of digitizing the industry and going paperless. It aims at increasing efficiency, data quality, cost-effectiveness, and sustainability (eliminating over 7,800 tons of paper documents annually) among other benefits to the air cargo industry.

Today, under the Multilateral Electronic Air Waybill Resolution 672, paper AWBs are no longer required. That means that it's still okay to use them, but IATA and its members mostly switched to the electronic version which is faster to process and exchange, easier to store and organize, and way better for the environment.

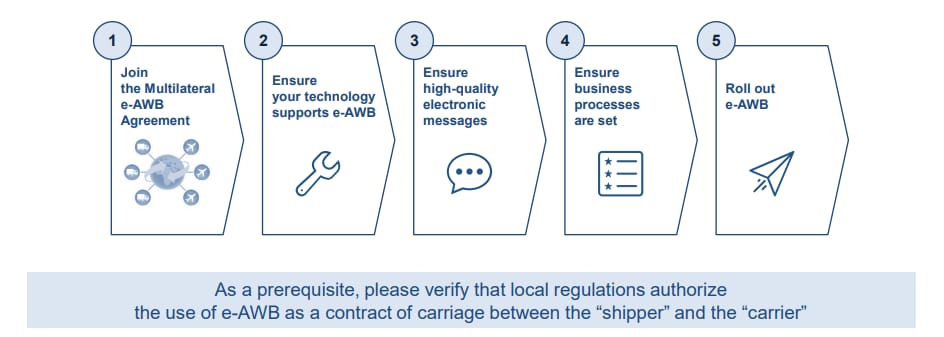

We have a very detailed guide for freight forwarders on how to integrate an e-AWB, so here we’ll only briefly list the main steps. The e-AWB implementation playbook by IATA provides the roadmap for joining the digital initiative.

5 steps of e-AWB implementation. Source: e-AWB implementation playbook

- Join the Multilateral e-AWB Agreement. Freight forwarders and airlines have to sign the agreement (free of charge) to enable the e-AWB exchange. You can check the list of participating airlines and freight forwarders in IATA’s Matchmaker. To enable e-AWB exchange, you’ll have to submit an activation request to every carrier you want to work with.

- Check if your technology supports e-AWB. IATA recommends using the Internet-based Cargo-XML format to exchange electronic information (there’s also an old Cargo-IMP standard, but it’s no longer maintained since 2014, though still in use). To get the specifications and guidelines, you can purchase IATA’s Cargo-XML Toolkit.

- Ensure high-quality electronic messages. To ensure data quality, you can either use the QA functionality provided by airlines or validate your messages with IATA’s free Cargo-XML AutoCheck tool.

- Set up the business processes. You might need to adapt your business workflows to the new paperless way of operating.

- Roll out e-AWB. Define your e-AWB roll-out strategy. The recommendation for airlines at this stage is to remember to activate your freight forwarders in the Matchmaker.

It’s totally up to you whether to build your own e-AWB system with the Cargo-XML platform or go with off-the-shelf e-AWB software. Let’s take a closer look at the second option.

e-AWB software

To streamline the shipment process, e-AWB solutions are expected to help with

- generating IATA-compliant electronic documentation,

- printing out paperwork if needed,

- exchanging messages with air carriers, and

- tracking shipments.

Such systems can come as standalone tools or as parts of comprehensive freight forwarding software. Here are some of the providers that offer e-AWB functionality.

e-AWB tools for freight forwarders: Riege, Magaya, Logitude, eAWBLink, and SmartAWB

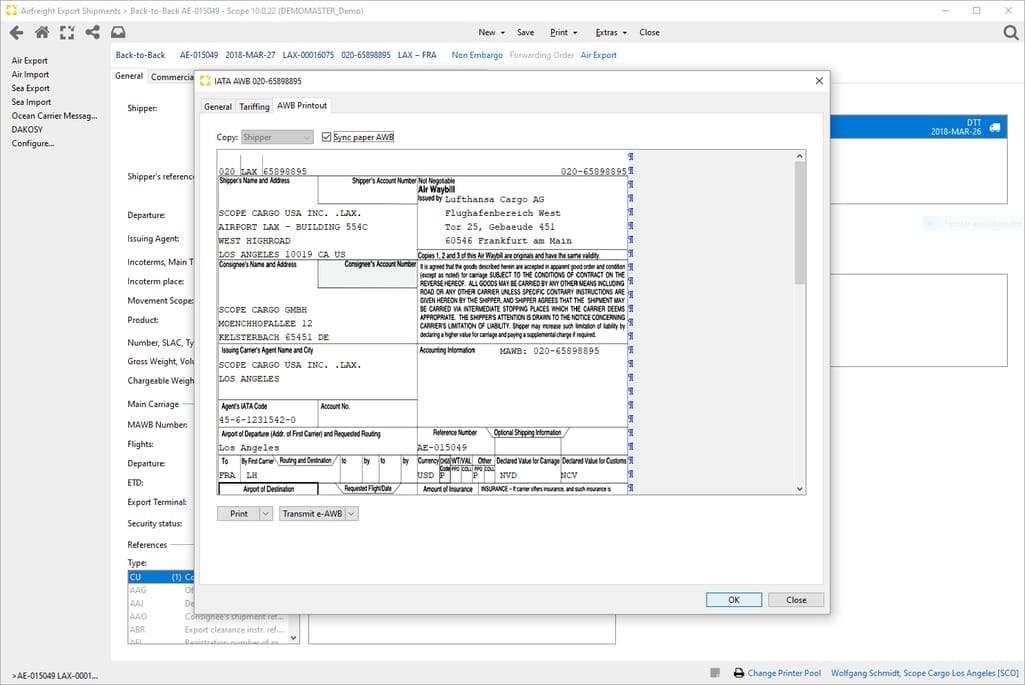

Scope by Riege Software is a full-blown freight forwarding platform for managing sea and air international shipments. Air freight functionality includes the automatic e-AWB creation, carrier AWB number administration, connection to Cargo Community Systems for message exchange, and more.

e-AWB editor. Source: Scope Air Freight Software

Magaya’s Digital Freight Platform automates multiple supply chain workflows, including carrier connections through AWB and e-AWB exchange.

Logitude also offers a full-fledged cloud freight forwarding platform with robust e-AWB services that not only include e-AWB generation and exchange, but also statistics monitoring, shipment timeline tracking, reporting, and much more.

eAWBLink was created as a result of the IATA, Descartes, and Mphasis partnership. This specialized tool allows users to create and manage electronic air cargo documentation, transfer it to airlines, and track and trace its status.

SmartAWB is a very easy-to-use, cloud-based solution that allows freight forwarders to generate, print, submit, and track e-AWBs.

Air cargo information exchange platforms: TRAXON cargoHUB, CCNhub, WIN, Cargonaut

An alternative to acquiring a specific tool can be integrating with one or several data exchange platforms. These global air cargo communities enable accurate and efficient information sharing, connecting all the parties involved in the transportation process (airlines, cargo agents/freight forwarders, ground handling agents, shippers, customs, etc.). Here are the biggest ones.

TRAXON cargoHUB by CHAMP is the largest air cargo community service that enables electronic connectivity between 100+ airlines and 3,000+ forwarders. It helps automate booking, operations, document handling, and customs processes. TRAXON supports all message types, among which are those related to e-AWB exchange, booking, status checks, error messages, and others. APIs are provided to connect to the platform.

CCNhub boasts over 10,000 users and offers data exchange solutions, a booking concierge, shipment and performance tracking functionality, localization services, Electronic Payment and Invoicing for Cargo (EPIC) system, and much more.

Worldwide Information Network (WIN) is a platform that caters mostly to independent freight forwarders, offering them easy connection to 160+ airlines for e-booking and e-AWB generation, exchange, and tracking. WIN can be accessed via the web or through a web service API integration. In addition, it offers a mobile app for shippers that supports shipment tracking, sending rate requests, and so on.

Cargonaut operates the Cargo Community Information Platform at Schiphol, the biggest Dutch cargo hub. It supports data sharing between all cargo parties and optimizes the related airport processes.

If you only work with a specific airline, you can check if it offers self-service freight management online. More about it in the next section.

e-AWB services from airlines

Most high-volume shippers turn to freight forwarding professionals to handle their cargo and deal with all the paperwork and customs hassle. In addition to deep industry expertise, freight intermediaries have established connections with carriers that facilitates and expedites the entire process, so airlines themselves recommend involving cargo professionals.

However, there’s nothing wrong with working directly with an air carrier. Some major airlines provide tools to book cargo space, get quotes, and manage shipments – including e-AWB generation and tracking. For example, check the myCargo tool by KLM/Air France or aacargo.com portal by American Airlines.

eAWB challenges

The penetration of e-AWBs grows steadily and since mid-2020, over 70 percent of air cargo professionals issue e-AWBs (at least according to IATA data). With all its benefits, it seems like a magic bullet and a game changer for the entire air freight industry. But is it really that shiny and perfect?

There are still a number of pain points that prevent the e-freight program from seamless functioning and global adoption. Here are some of them.

Regulatory constraints. Some government regulations place limitations on air industry digital initiatives, especially regarding security issues. As a result, many airports still rely on paper documentation in their workflows.

Poor standardization. The e-AWB procedures are still not completely harmonized between carriers, forwarders, ground handling agents, and other parties involved.

Legacy or lacking technology. Most industry players still use outdated technology that’s not able to generate and exchange e-AWBs. For example, airlines rely on the legacy EDI-based CargoIMP message format that presents a number of limitations compared to the newer CargoXML, which is more flexible and secure. Meanwhile, independent forwarders are often reluctant to adopt new technologies because of associated costs (even though some airlines charge more for processing paper documentation).

Low message quality. Often, electronic messages lack required attributes and can’t be processed right. Obviously, instead of expediting, that slows down the entire process.

Connection complexities. When forwarders deal with multiple airlines, they have to connect with each one separately, submitting the activation request and synchronizing the message exchange process.

Maria is a curious researcher, passionate about discovering how technologies change the world. She started her career in logistics but has dedicated the last five years to exploring travel tech, large travel businesses, and product management best practices.

Want to write an article for our blog? Read our requirements and guidelines to become a contributor.