Fostering innovation in an organization requires a skilled and structured approach. If you can’t see how different systems within your company – both business and technological – work together to reach your goal, don’t be surprised when IT projects don’t deliver their sought-after value. Just like any transformative change, modernization requires a holistic and systematized approach, a groundwork for every stage of this gradual process.

Enterprise architecture is the roadmap – the practice that encompasses the assessment, planning, and designing of your business’s use of technology to achieve its goals. The people responsible for this seamless transition are enterprise architects. Their broad range of skills along with their ability to find a common language with both stakeholders and IT experts allow them to guide a company to its desired state. We’ve already discussed the role of enterprise architects in business and now we’ll highlight the tools and approaches they put to work in planning and visualizing the transformation.

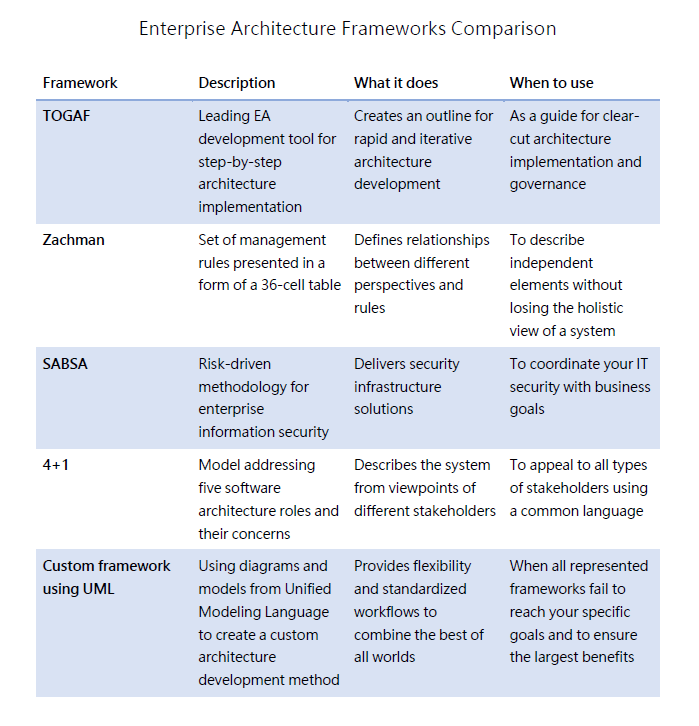

Enterprise architecture considers organizations complex systems. To manage this complexity, enterprise architects use standardized methodologies or frameworks that help them document a system’s behaviors in a commonly recognized way. Let’s quickly compare the most popular frameworks.

Enterprise architecture frameworks compared

Now, we’ll dive deeper into functionalities and use opportunities for each framework. Read on to learn how you can apply them for your organization.

TOGAF - a Standard Framework for Continuous Architecture Development

The Open Group Architecture Framework or TOGAF has been developed by more than 300 enterprise architects from leading companies including Dell, Cognizant, and Microsoft. TOGAF development traces back to 1995 and its current version 9.1 embodies all improvements implemented during this time. The tool has a common vocabulary and is meant to support all levels of architecture for enterprises both large and small.

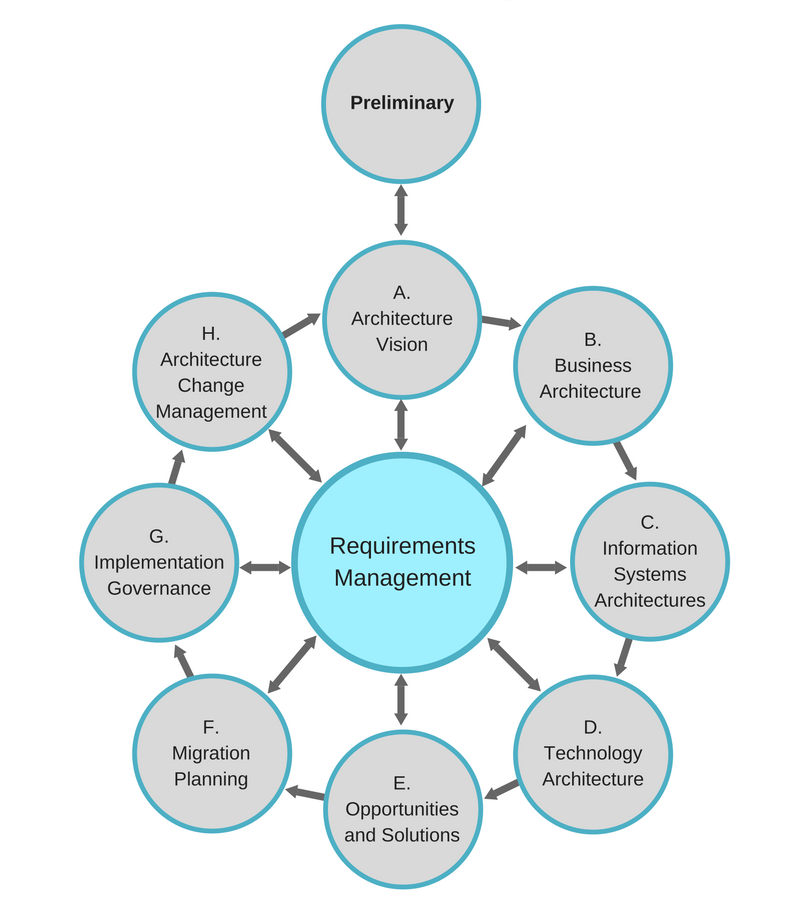

The TOGAF’s established method for rapidly developing an architecture (Architecture Development Method or ADM) is a step-by-step process that describes ten phases arranged in a cycle. In the center of the process you can find Requirements Management – the stage reflecting the ongoing process of aligning changes and requirements of each phase.

TOGAF Architecture Development Method

What do its elements represent?

Preliminary Stage - defining the principles, concerns, and requirements for a future architecture Architecture Vision - choosing architecture scope and methodologies to align with stakeholders Business Architecture - using modeling methods to describe an Architecture Vision Information Systems Architecture - modeling Data and Application Architecture Technology Architecture - transforming the description of a system into the basis of architecture implementation Opportunities and Solutions - defining the main steps towards changing your current architecture to the target one, the basis of the Implementation Plan Migration Planning – describing the estimated costs, timeline, and roadmap of implementation Implementation Governance - assigning governance functions for different stages of architecture deployment Architecture Change Management - providing monitoring for technology and business changes

When would you use TOGAF?

- To transform an organization’s architecture and processes in a controlled manner

- To repeatedly align your processes with current goals

- To support an architecture development process at all stages, from evaluation of key requirements to actual implementation

TOGAF has been adopted by 60 percent of Fortune 500 companies. Due to its extensiveness, the framework is highly adaptable, and it nurtures agility and collaboration. However, as with any widely recognized methodology, it has earned some criticism because of its theory-focused approach that few can turn into practice. So, remember, that despite its popularity, TOGAF is not a cure-all and should be used as a guide rather than an actionable plan.

Zachman Framework - a Cross-Dimensional Matrix to Align Roles and Ideas

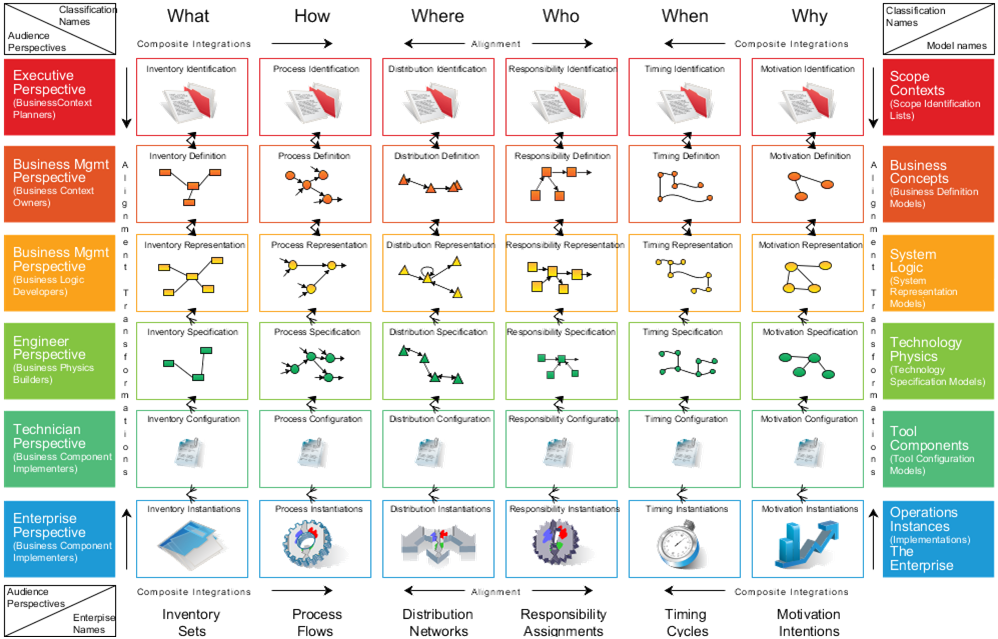

The Zachman Framework is not a methodology but rather a template describing how different abstract ideas are viewed from different perspectives.

This two-dimensional matrix consists of six rows (perspectives) and columns (fundamental questions), its intersecting cells describing representations of the enterprise in a detailed and structured way. Zachman Framework is normalized, and its rows and columns cannot be removed to keep the holistic overview of the system. Still, it’s flexible enough to work for a project of any scope to clearly focus on each element and its purpose, and build contextual relationships between cells. The finished scheme is not an architecture; it’s a tool helping manage and organize one.

Zachman Framework Source: NoMagic

What do its elements represent?

The players represented in rows are:

Executive Perspective - a planner seeking information about a system’s size and costs Business Management Perspective - an owner wanting to know how business processes interact Architect Perspective - an architect determining how software functions represent the business model Engineer Perspective - a contractor applying specific technologies to solve business problems Technician Perspective - a programmer given instructions Enterprise Perspective - an operational system itself

The columns can be described as:

What? - enterprise data each row has to deal with How? - an organization’s functions and processes Where? - geographical locations, logistics, interconnections When? - business cycle and events triggering business activities Who? - organizational units and interaction between people and technology Why? - the translation of business goals and strategies into specific means

When would you use Zachman Framework?

- To concentrate on independent objects without losing the vision of the holistic perspective and relationships between objects

- In conversation with stakeholders to clarify what each level should focus on without delving into technical aspects

- As a documentation tool that can be easily combined with other models

- To simplify communication within the team

- To look at what perspectives you’ve already described and what’s missing

SABSA - a Risk Management Framework to Align Business and Security

SABSA (Sherwood Applied Business Security Architecture) is an operational risk management framework that includes an array of models and methods to be used both independently and as a holistic enterprise architecture solution. This is another highly customizable and scalable framework – it can be adopted in a small scope and then incrementally implemented on an enterprise-wide level.

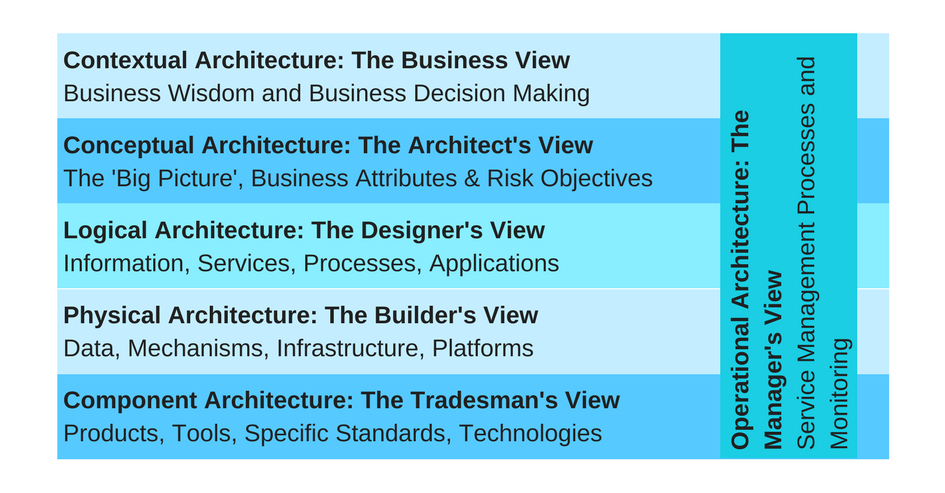

SABSA closely follows the Zachman Framework and is adapted to a security focus. SABSA uses Zachman’s six questions that we’ve already described to analyze each of its six layers of security architecture development.

SABSA’s six layers of security architecture

When would you use SABSA?

- To avoid mistakes by documenting them in advance and keeping them in mind while creating an architecture

- To align your security architecture with business values

- To set up quantifiable metrics that track business performance rather than technical ones

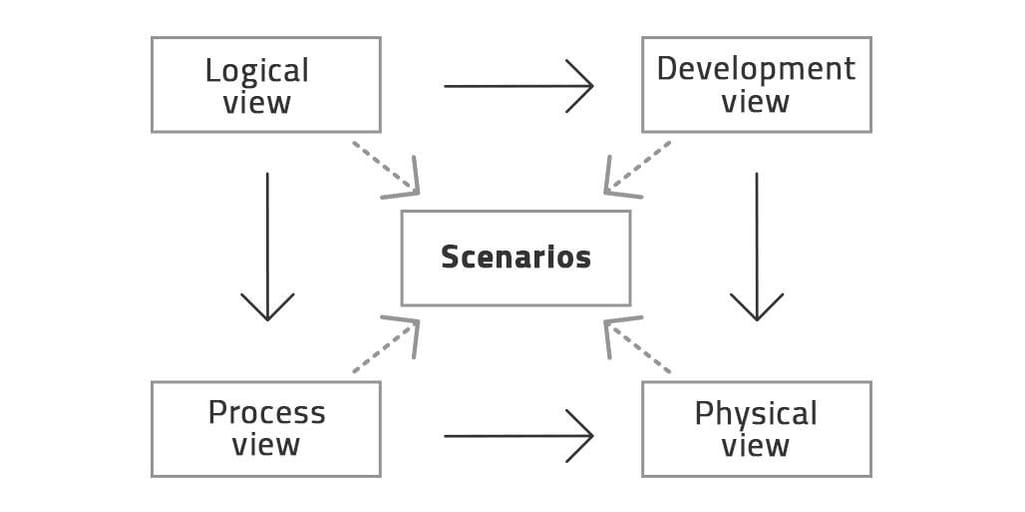

The 4+1 View Model - a Minimalist Tool for Addressing Different Stakeholders

The basic idea behind the 4+1 methodology lies in dividing different aspects of software systems based on the interests of different stakeholders. This is another framework that resembles Zachman’s approach. The model’s creator Philippe Kruchten believed that by separating an architecture into distinct views, it will be displayed from a viewpoint of each stakeholder, be it a customer or a developer.

It’s four main views are described as:

Logical - represents what a system should functionally provide, system components and their relationships Process - shows a system’s performance, scalability, workflow rules Development - focuses on software modules, packages, and environments used Physical - considers how software is mapped to hardware

The fifth view – Scenarios or Use Cases – represents the high-level view of the whole system and illustrates an architecture’s consistency and validity. This view is relevant for all stakeholders.

Scenarios or Use Cases view of the 4+1 framework

When would you use the 4+1 model?

- To prioritize different views and simplify the organization process

- To integrate with other tools such as TOGAF

- To easily document both individual projects and a company’s whole IT architecture

Creating a custom EA Framework using Unified Modeling Language (UML)

Most enterprise architecture frameworks offer a limited number of viewpoints and aspects, so it’s reasonable and common to use them in combination. None of the proposed models can include all measures and meet every organization’s needs. However, this allows enterprise architects customize documentation and create an independent overview of a system.

Unified Modeling Language (UML) is a descriptive visual language providing scalable diagrams used for standardizing software development. It’s easily expandable and customizable for different business domains using an extension mechanism – UML Profile. Enterprise architects use stereotypes, tagged values, and constraints to tailor the language to specific environments thus ensuring that the finished model will address corporate-specific requirements.

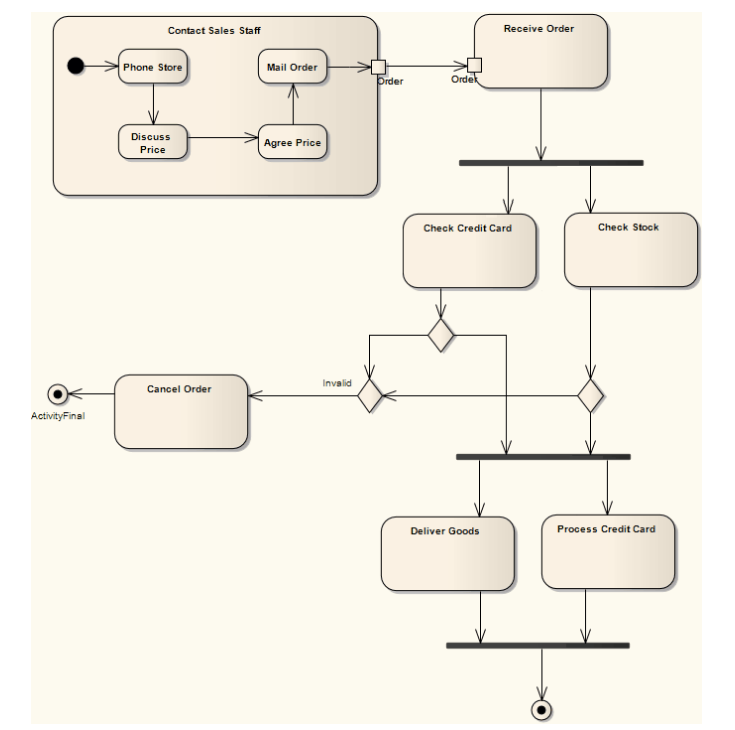

Some generic UML diagrams include the Deployment Diagram, visualizing a system’s execution architecture; the Activity Diagram, that models behaviors of the system and how these behaviors are related; and the Sequence Diagram, representing workflows and cooperation.

An example of an Activity Diagram Source: SparksSystems

UML models allow businesses to develop a set of processes and use cases to visualize an enterprise architecture overall and each system within it. It’s a complicated tool that requires training to operate and adjust to a company’s needs, but the benefits of this approach are correlated with the enterprise architect’s effort.

The problems with EA frameworks

Almost 30 years after the creation of the Zachman Framework – the oldest of the currently used EA tools – a question has arisen: Do frameworks bring any value or do they cause harm? Here are the main concerns surrounding the use of enterprise architecture frameworks today.

- Documentation is not comprehensive

Despite numerous updates to the most popular frameworks created in the 80s and 90s, their modern versions are still considered impractical and outdated. Moreover, creating and maintaining EA documentation requires resources that are not always available in the agile environments of many innovative companies.

- They are time-consuming and lack flexibility

Most EA frameworks are less dynamic than modern business toolkits such as Business Model Canvas. They take time to plan out, are not change-friendly, and require training to develop and present. Being more about documentation than real action towards innovation, they tend to slow down the process with excessive use.

- Complete integration is impossible

The limitations of each framework don’t provide an opportunity for seamless integration with a company’s new and existing systems and call for notable adjustments that require additional resources.

These concerns don’t necessarily mean that three decades of practice has led to EA frameworks becoming obsolete. Just like any formalized approach, Zachman or SABSA are criticized and augmented, introduced at the beginning and throughout the process, and used by enterprise architects in different ways. Be sure to take the most advantageous elements of a framework and work around the constraints.

Conclusion

Enterprise architecture frameworks are valuable for planning and visualization. They are especially helpful at the early stages of architectural change to lead the conversation with stakeholders and visualize the outcomes of business and IT alignment. However, they are still just toolkits for people responsible for preparing the roadmap to change.

When looking for an enterprise architecture practice, note their experience and capabilities outside the TOGAF certification and listen to their recommendations regarding frameworks and tools relevant to your particular case.

Maryna is a passionate writer with a talent for simplifying complex topics for readers of all backgrounds. With 7 years of experience writing about travel technology, she is well-versed in the field. Outside of her professional writing, she enjoys reading, video games, and fashion.

Want to write an article for our blog? Read our requirements and guidelines to become a contributor.