Here’s a cool story about a button, or the button, to be precise, as told by Daniel Tonkopiy, an entrepreneur from Ukraine.

Back in 2011, when US citizens had already been enjoying OpenTable online restaurant booking, Ukrainians had to book a table by phone. Daniel and his team assumed it would be a great idea to bring a slice of digital transformation to Kyiv by adding the table-booking button to local restaurant websites. He didn’t realize then the road that lay ahead.

First, most restaurants didn’t use CRMs and resorted to tracking reservations in notepads, you know, paper and pencil. So, the team had to build a custom CRM for restaurants reservation management.

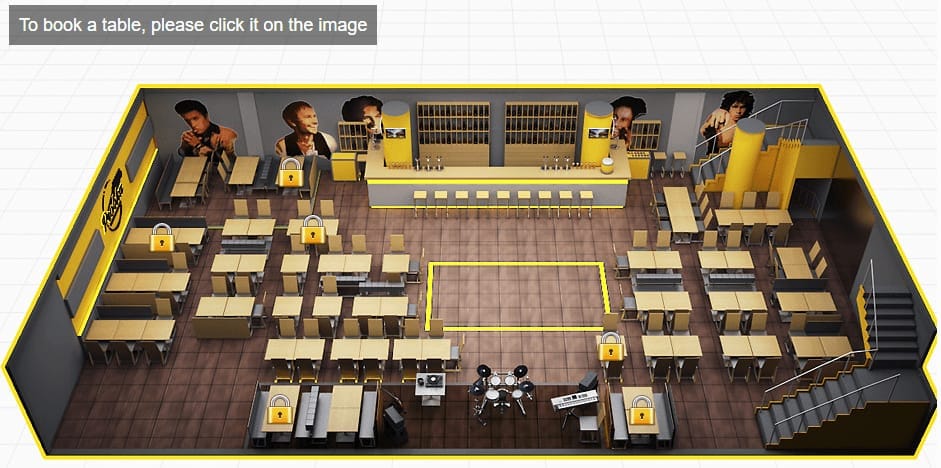

To enable booking, they also had to design interactive 3-D maps for each restaurant, detailed enough to let users catch the look and feel of the place they were going: near the window, or by the bar, or by the stage with deafening speakers.

Like this. That’s how it looks at Letsbar booking service today

Like this. That’s how it looks at Letsbar booking service today

Finally, they engineered the button itself with CRM integration and phone messaging to confirm reservations.

It took a year of product management, design, engineering, and negotiations with stubborn restaurant owners to launch the button.

And… they got a whopping four reservations in the first week.

Most people kept on using phones. Given that the business earned $1 per reservation, the button could only be viable at scale.

After getting about ten reservations per week in the first month, they decided to analyze the market. Out of nearly 2000 Kyiv restaurants, only about 20 needed reservations in advance… And most of their visitors were just fine with making phone calls.

There was no market.

And it took them a year to realize that. After some time, Daniel found that there was an open source button with the same but slightly limited capabilities.

“I was in panic” - writes Daniel - “We’ve spent an entire year of everyday work, a whole lot of money, mental power, emotional stress, individual contributions, but the main thing - we’ve lost time, 12 months of several people’s work on a project, the result of which we could achieve in mere two weeks.”

Here’s how Andy Rachleff, a co-founder of Benchmark Capital, suggests thinking about the market:

When a great team meets a lousy market, market wins.

When a lousy team meets a great market, market wins.

When a great team meets a great market, something special happens.

The market always wins. Great ideas, great teams… well, not so much. The button was a great idea by a seemingly great team, but it didn’t have the market.

So, finding a product/market fit and documenting it with a product strategy is what we’re going to talk about in this article.

A little thing to keep in mind, a product here is any piece of software that solves a customer problem, be it a corporate tool with multiple interaction flows, a mobile app, or even a single feature in a larger application.

What is a product strategy?

A product strategy is what you are going to do with your product in the near term, usually within a year.

Traditionally, a product strategy answers three main questions:

- What do we sell? (product)

- Who do we sell it to? (market)

- How do we know if we sell it successfully? (goals that are translated into product metrics)

These three questions can be further divided into eight main components (or dimensions) of a product strategy. We’ll take the key ones suggested by Sachin Rekhi, business consultant and a former LinkedIn product manager.

- Target audience and the problem that the product must solve

- Market size

- Competition

- Value proposition

- Strategic differentiation

- Acquisition strategy

- Monetization and pricing

- Key performance indicators

We’ll go over them in detail below. These are just essential ones. Some frameworks, like business model canvas, suggest additional dimensions, but ultimately, it’s up to the business to decide which critical points must be covered. Use this business model canvas template to learn more about its different dimensions.

The reason for creating a product strategy is to capture a product/market fit.

What’s a product/market fit?

A classical definition of the product/market fit was suggested by Marc Andreessen, founder of Netscape and Andreessen Horowitz:

“Product/market fit means being in a good market with a product that can satisfy that market.”

In other words, you must create a product good enough that at least some real people on Earth want to buy it for the price you can afford (harder than it sounds). The example of the button clearly shows what happens when you don’t have a product/market fit.

Eight main components of product strategy

As promised, we get back to what goes into a product strategy.

First, you don’t create a strategy. Rather, you research it.

If you wake up in the middle of the night with the bright idea of a startup, wait until morning and start researching, before inviting your friends to the garage.

Research sounds complicated, and if you look at industry giants, it really is.

You may have an army of market analysts, a Netflix-grade A/B testing pipeline, and a machine learning bot checking social media to analyze customer sentiment. This technological singularity stuff can help create a solid and weighted product strategy.

But you can outline your strategic points having an old laptop with jamming buttons. And it’s fine. Strategy in the modern world is iterative and you have to revisit it regularly. If you get something wrong today, consider it was just a hypothesis that you will refine tomorrow.

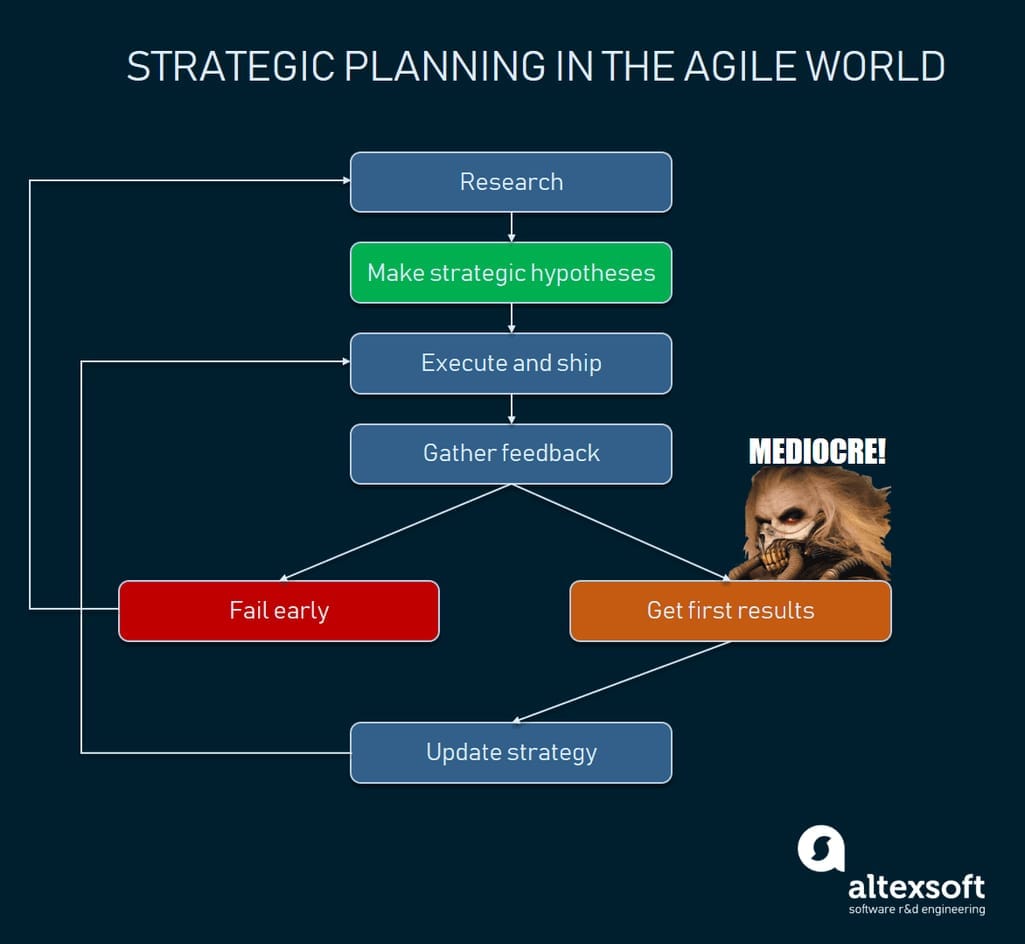

Strategic planning requires constant refinement of your hypotheses

Strategic planning requires constant refinement of your hypotheses

That said, let’s dive into the details of the research.

Find your perfect customer and their problem

If you trace back the stories of modern and successful digital products, you’d be surprised to find two common traits.

The initial problems that this product solved were:

1) very narrow to a specific group of people

2) very… problematic.

The latter means that the problem was hard to solve otherwise and the solution gave an incredible boost to end-customer productivity/savings/comfort, etc.

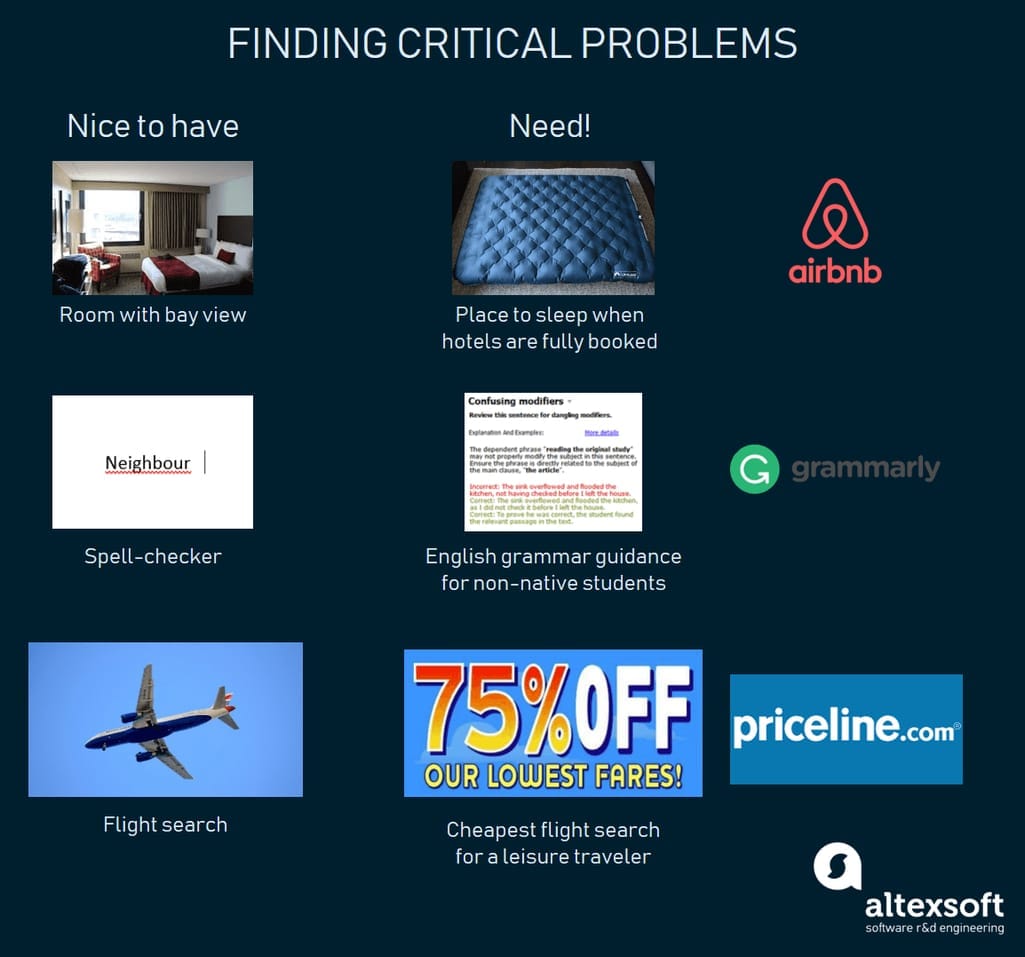

Grammarly, a popular AI-based English editor, first targeted university students that weren’t natives and sought some language guidance. Primitive spell-checking that Microsoft Office suggested didn’t count. Airbnb, or Airbedandbreakfast back then, initially suggested inflatable mattresses and breakfasts to people who were coming to the city when all hotel rooms were fully booked, usually during massive events like conferences. There were no places to stay at all!

All three nailed the finding of critical problems

All three nailed the finding of critical problems

The button story shows how little the team knew their customers (they used phones) and how poorly they understood the market size (only 20 restaurants needed reservations).

So, let’s have a look at the most basic things you can do here:

Surprisingly, be a target audience. If you are a target customer, know that you’ve hacked this part. You understand the real critical problem with all the specifics that you can prioritize. Many successful products solved the real issues of their creators.

Slack, a superstar team messenger, has grown from an internal product of a globally distributed team of engineers: They needed efficient communication. Even today the Slack team first tests its features on themselves. Amazon Web Services, the leading cloud provider, emerged from the infrastructure that solved Amazon online store tasks.

Find your perfect customer. If you don’t belong to the target audience, you’ll have to define who your perfect customer is. A common recommendation here is the same: be as specific as possible. Paladin, a 2015 startup that raised $3.75 million, creates an opportunity management tool for lawyers who do pro bono work. Your total addressable market may be larger but try articulating a narrow audience who couldn’t manage without your product.

Run interviews. There’s no better way to refine the problem statement than running interviews with your perfect customers. Check our article to get an exhaustive guide.

Create user personas. A user persona is much like a CV, but with many personal details: age, gender, lifestyle, habits, work, income, and anything that may help you look at the world from a customer’s eyes and prioritize the problem you solve better. You’ll also be able to leverage your user persona profiles further when you get to designing a product.

Separate end-users and customers in B2B. A common case that we constantly face here at AltexSoft is that B2B products cater both to people who make decisions about a purchase and actual users. Quite often, these may be two completely different groups of people. If you’ve ever worked for a large employer, you likely know this bitter taste of corporate software UX. Think, whose problem you really address.

Once you’ve narrowed down your ideal customer, the one who’ll install your product first on a new device, you should estimate whether these people really exist and how many of them are out there.

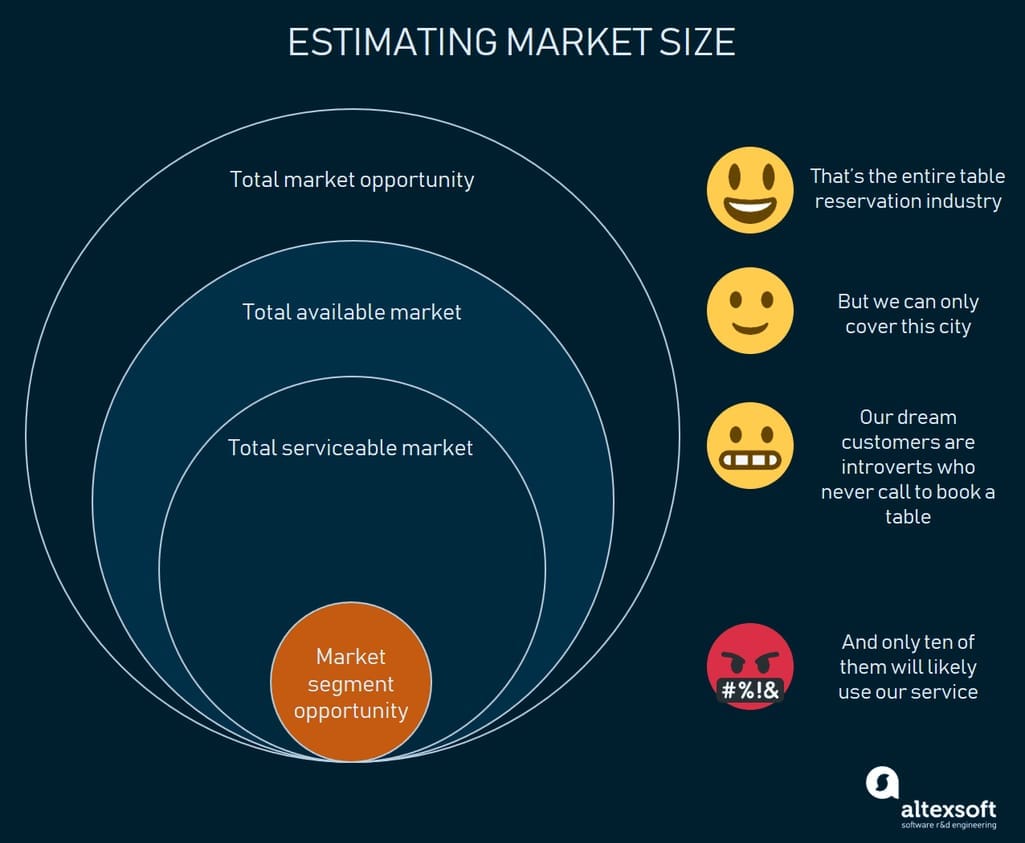

(Guess)estimate market size

There are many approaches to estimating market size. Let’s focus on the main ones that you should combine:

Top-down approach. You can google statistical and open sources of information about your entire industry and its purchasing power. Market research statistics, government stats, public reports, and wiki would work.

- First, figure out the entire purchasing power or a total market opportunity that you dream of conquering,

- Narrow it down to your segment (total available market),

- Then narrow it down even further to the purchasing power of your perfect customers (total serviceable market),

- And finally estimate how much your perfect customers will bring to you, given that some of them will stick to your competitors (market segment opportunity).

Be as realistic as possible

Be as realistic as possible

Bottom-up approach. Frankly, you’ll find yourself guesstimating a lot. The information may be sparse and you have to combine multiple approaches to get to the point. A bottom-up approach starts with exploring your customers - possibly existing ones - and then considering how many you can acquire with your product. In other words, if your team of engineers enjoys a DIY time-tracking tool, you may consider how many people there are - just like your engineers - who may be willing to buy your tool.

If your market is reasonably big, then you’re on the right track.

Explore competition

There are two main reasons to look closely at your competition when you define your product strategy:

1. Estimating market size. Yes, to define your market segment opportunity, you have to know who your competitors are. Then you’ll be able to estimate how much of the market you can conquer. This is especially important if you enter a mature market and consider critical differentiation features.

2. Understanding how your perfect customers manage without you. In emerging markets - where there are no direct competitors - you should take a wide-ranging look at different ways the problem that you target is solved. People may still be using spreadsheets, while you consider building a shiny SaaS dashboard. Or there may be a legacy monstrosity with a cryptic UI. It gets easier to specify your value proposition, given these competitors.

Make a promise with value propositions

Don’t believe the people who say that a value proposition is about the cool features of your product. In reality, it is:

The promise of the value. A value proposition is a promise that you are going to change the life of your customer for the better. It also must show exactly how this change is going to happen.

Why competitors can’t. On top of that, it must imply what’s wrong with your competitors (without directly saying it) or keeping the status quo (if you don’t have direct competitors).

Compelling. You’re going to show your value propositions to customers. So, take care of wordsmithing.

True. But don’t overpromise. It still must realistically depict the brand new world with your product.

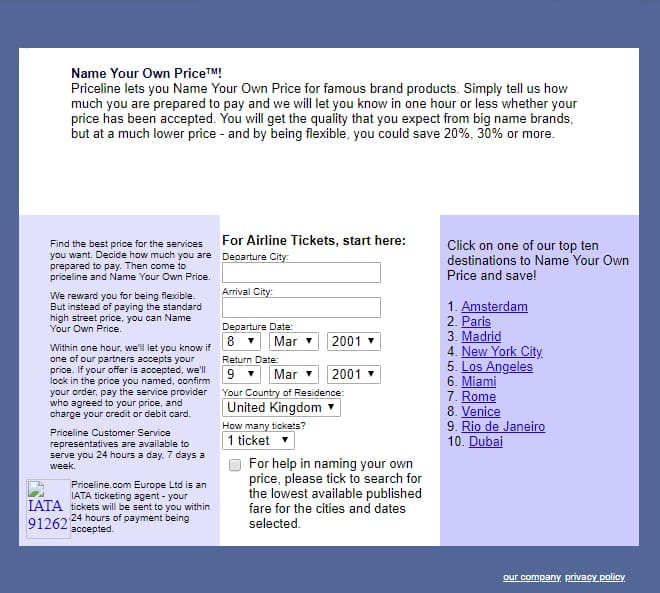

Back in the times when the Internet was advertised on TV, Priceline, a flight booking website, said:

Name Your Own Price!

Simply tell us how much you are prepared to pay and we will let you know in one hour or less whether your price has been accepted. <...> you could save 20%, 30% or more.

The Internet was more verbose before fancy UIs arrived, but let’s acknowledge, it’s a good copy

The Internet was more verbose before fancy UIs arrived, but let’s acknowledge, it’s a good copy

There may be multiple value propositions but try to limit them to three as improving and iterating upon multiple ones is increasingly difficult.

Answer how to deliver on the promise: strategic differentiation

But how are you going to deliver this value? Your assets and unique capabilities are your strategic differentiation.

Priceline was sweeping flight inventories looking for tickets that were about to expire. And you’ve guessed it, airlines were ready to sell them for nothing just to keep aircraft to capacity.

When you consider strategic differentiation, define which advantages you have up your sleeve that will enable the value:

- Pixel phones have almighty Google’s AI inside a questionably designed box

- There were cloud storages before, but Dropbox made it possible for humans to use them thanks to its UX

- Speaking of our clients, not only does Fareboom sell flights, it can predict fares and let customers choose when it’s better to buy a ticket

- Eventually, your product may be just cheaper

Define your customer acquisition strategy

Regardless of how great your product may be, nobody will buy it until you market it. We’ve broadly discussed product marketing in a dedicated article. Let’s recap the main points:

1. Define the target audience. If you’ve nailed the target audience part, consider this point as done. Your buyer persona will be the main source of information to assume which channels of lead generation and acquisition are going to work better.

2. Define your key channels and keep them focused. What are the shortest ways to find your customers and explain to them how great your product is? Your choice depends on a clear understanding of your market.

If you’re building a SaaS product for a handful of executives in a very specific market, you don’t need to pre-roll YouTube commercials: It’s better to contact your prospects directly. If your buyer persona spends most of their mobile time on Instagram, you know which web advertising channel to choose.

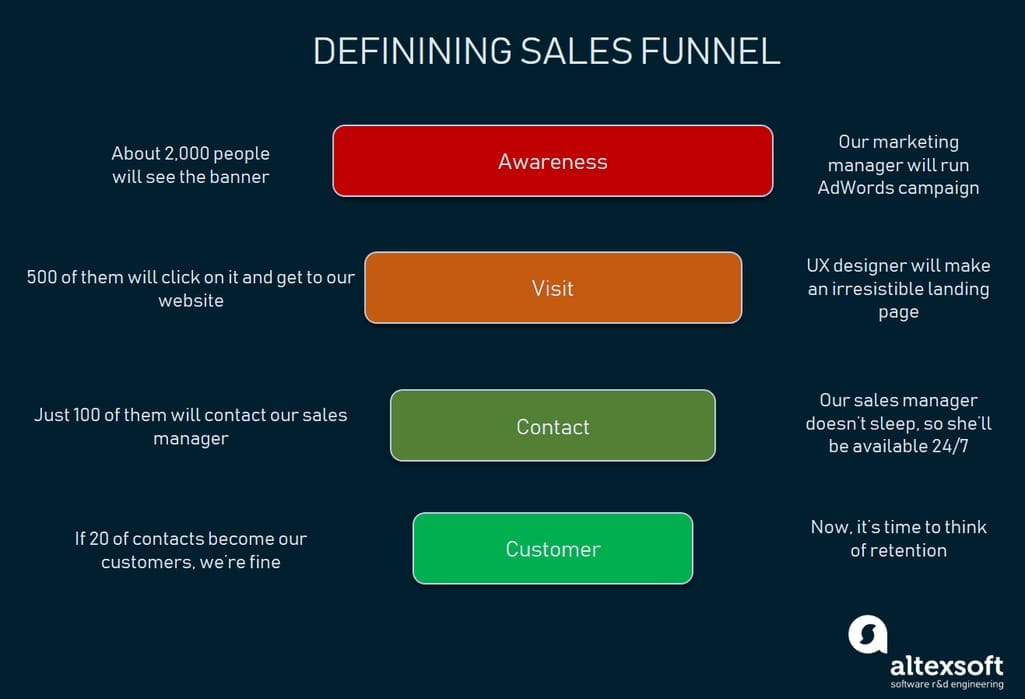

3. Outline your sales funnel. A funnel documents the path of a customer from the moment they get to know your brand (awareness) to a purchase (customer). Suppose precisely how you're going to lead a customer through this trail and who’s going to be responsible for each stage.

If you diversify your sales channels (which you should), you may have multiple funnel variations

If you diversify your sales channels (which you should), you may have multiple funnel variations

4. Calculate your customer acquisition cost (CAC). You may dream of running multiple web campaigns, visiting conferences, writing a blog, and booking an airplane with a banner that will fly over your prospects’ houses. In reality, you have to understand how much this all is going to cost and which channels you should prioritize. A common formula:

CAC = marketing cost/number of acquired customers

If you know your CAC, you can presume the viability of your acquisition strategy.

5. Make it sustainable. You can write a couple of posts on your website and call it a blog. However, if you can’t regularly publish new posts, your blog-driven awareness isn’t going to work in the long run. Make sure that you have enough resources to make your acquisition strategy sustainable.

Choose monetization and pricing

There are many monetization methods: subscriptions, transaction fees, freemiums, etc. Essentially, the type of product you sell will help you choose the best one.

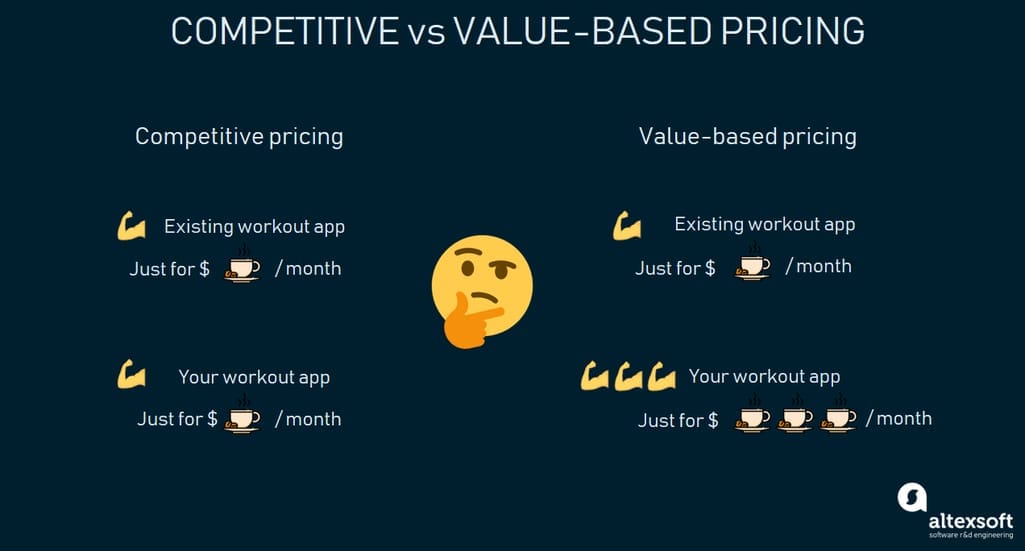

A lot more difficult question is how to price your product or, let’s put it this way, how much your customers are ready to pay at this point.

Competitive pricing. You can start with competitors and set up the price based on the expectations of customers who already use such products. The key drawback here is that it’s harder to maximize the revenue.

Value-based pricing. This strategy works better in nascent markets, where customers don’t have specific expectations and your product may bring exceptional value to them. The higher the perceived value, the higher your price. This doesn’t mean though that you just crank the price as much as you can. You may apply additional strategies like setting a temporary price to let your customers assess the value and then you’ll be able to set the bar higher.

Value-based pricing is much harder to handle and justify

Value-based pricing is much harder to handle and justify

Measure success with key performance indicators (KPIs)

Finally, you have to know if your product is successful. What are the measurable goals?

A good practice is to prioritize those KPIs that match your product’s life cycle stage.

MVPs and newly launched products. You shouldn’t expect to receive an impressive ROI at this stage. So, acquisition and engagement metrics such as customer acquisition cost, traffic, and customer satisfaction are the first ones to consider.

Growing products. As you grow further, you may expand your focus to monetization metrics (ROI, net profit, revenue growth rate).

Mature products. If your product has reached profit stagnation and you have many competitors trying to bite off a piece of your market, you may also consider retention KPIs and net promoter score.

To learn more about ways to track your product success, check our article on the product metrics and KPIs menagerie.

That said, the best practice here is to avoid borrowing best practices. When you look for measurements of your success, consider the inner quirks of your product. If your application automates a chunk of manual work, measuring engagement with an average session duration or the number of user actions is weird. But net promoter score and user satisfaction are the things to keep an eye on.

How to document product strategy

Or, what does a strategy look like?

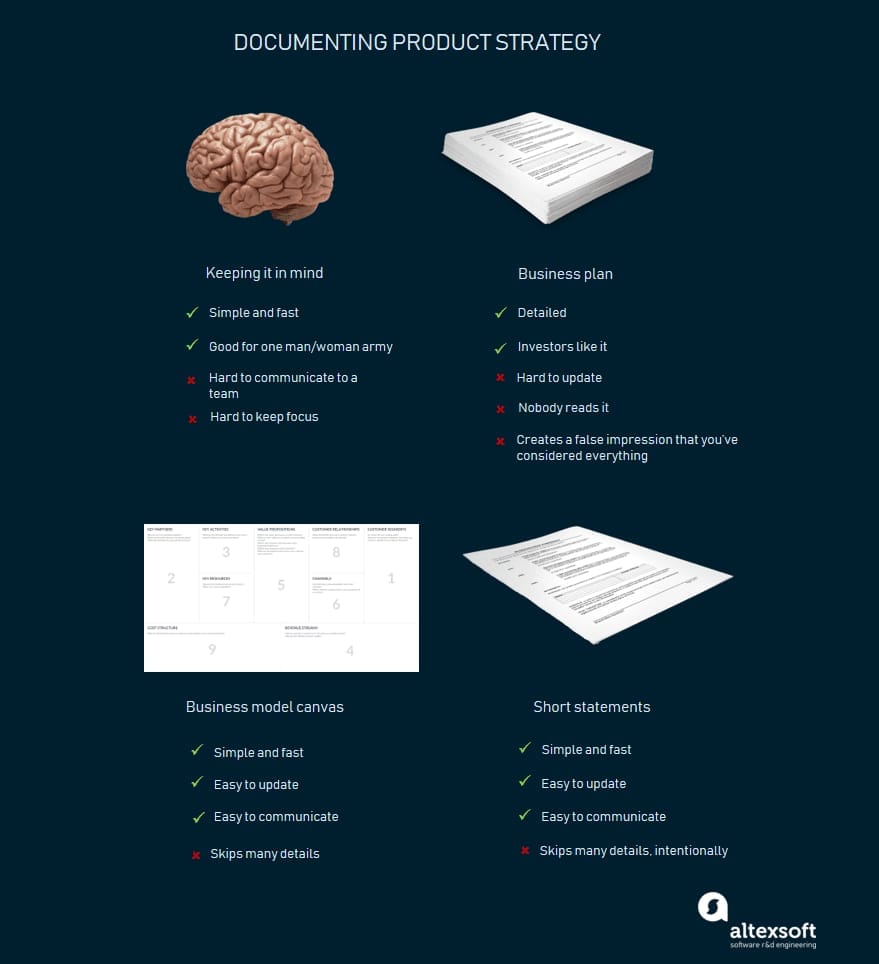

You keep it in mind. You may not document it all. Arguably, it’s a bad approach as you should communicate the strategy to your team and have it at hand as a reference. But if you’re a one man/woman army and you know what you’re doing, it’s fine. You’ll document it later.

You make a business plan. If a business plan sounds to you like something from the waterfall era with many pages that nobody bothers to read, you aren’t far from the truth. However, a business plan is still a viable option to capture many things with many details. But the problem remains: It’s hard to make a traditional business plan accessible to all your team members.

You make a business model canvas (BMC). Here’s a millennial approach to strategic planning. BMC is a simple way to capture all important things on a single board and communicate them to a team. Check our business model canvas article. It’s detailed and has many cool examples.

You write short statements. You can go even simpler than that and just outline each key component in 2-3 sentences. This will also be a lean way to document and, more importantly, communicate the strategy to a team.

Choose your poison

Choose your poison

What happens after defining a product strategy

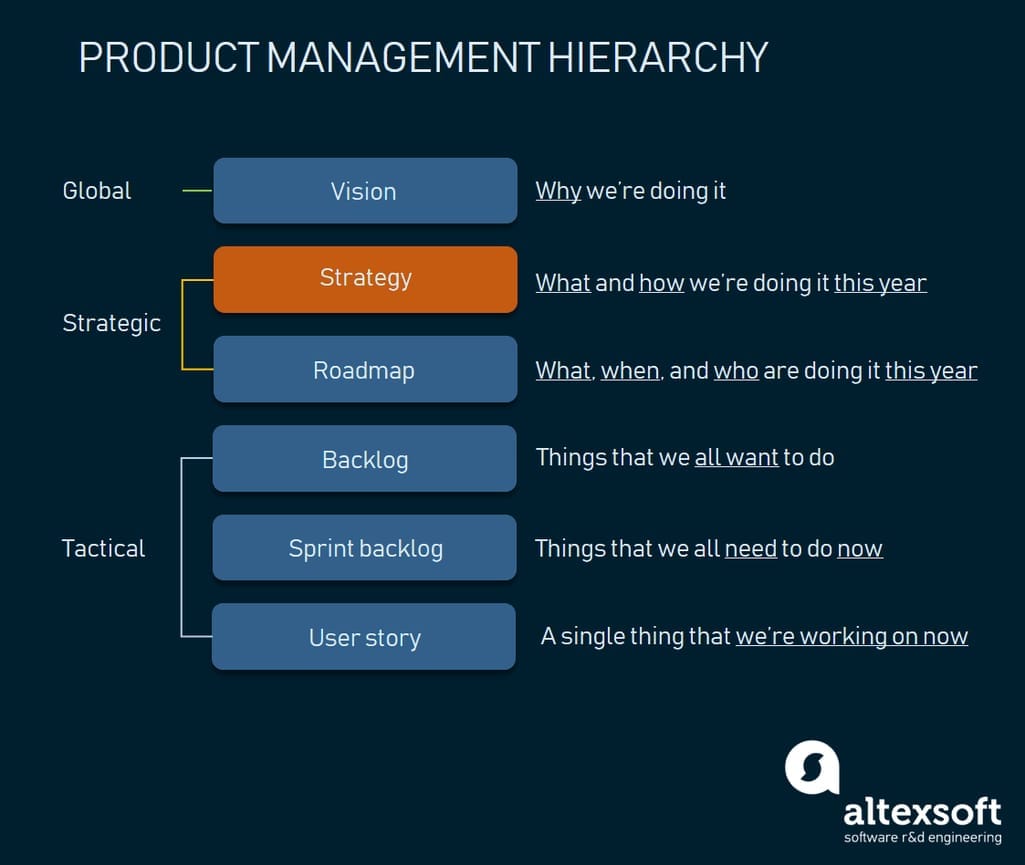

A product strategy is a part of a larger product management set of activities that you can read about if you click the link.

Product strategy is a high-level planning tool that’s a bit more precise than vision. If you talked to the Valley entrepreneurs, you’d learn that the vision is how the world is going to change with your product. For instance, Airbnb’s vision is “to create a world where anyone can belong anywhere.”

You may not be that audacious, but the vision is the most abstract tool in product management. It sets a long-term objective and steers the team’s efforts towards it, constantly reminding of a general direction.

A product strategy is more specific and defines concrete things, usually, in a year-long perspective that supposedly will get you closer to your vision.

After you’ve done a strategy, you can create a product roadmap

As soon as you have a vision and a strategy, you should finally get to outlining the roadmap. Then you can start with tactics and actual product development process, including crafting user stories in a product requirements document (PRD).

Here's us explaining how everything works together in a video:

fhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7j4WGVAsf4Y

At this point, you may be thinking: But what about the product itself? Why should I focus so much on the market, problems, competitors, instead of the product itself and its core features?

Here’s an interesting exercise. Go to producthunt.com, screen through trending ideas, and try explaining which problems they solve. Who does experience these problems?

Starting your strategy with product/market fit will help you vet, specify, and iteratively refine your product, keeping the focus.

As you’ve heard many times before, the main reason a product fails is that it solves non-existent issues, the challenges of non-existent people, or doesn’t solve anything.