Global distribution systems (GDS) are powerful middlemen connecting suppliers and resellers in the travel industry. From their origins in the mid-20th century to their transformation into global commerce hubs, GDSs have continuously shaped how we sell travel.

This article won`t reveal anything new to people who have been in the travel business for a long time, but it will provide newcomers with a comprehensive overview of GDSs' history, functionality, and relationships within the travel ecosystem. We'll also explore how these platforms are evolving in response to changing industry demands and the rise of new technologies. By the end, you’ll clearly understand why GDSs remain indispensable and where they might be headed.

What is GDS?

The global distribution system (GDS) is a computerized platform that serves as a key intermediary between resellers and service providers in the travel industry. It aggregates data from airlines, hotels, car rental companies, and other suppliers, acting as a single point of access to many travel products globally.

GDSs do not have interfaces for the general public, so travelers can’t directly see the aggregated content online. The primary customers are online travel agencies (OTAs), travel management companies (TMCs), brick-and-mortar travel agencies, and other travel businesses.

Although global distribution systems offer access to various travel services, they are most often used to purchase airline tickets and remain the key sales channel for most full-service carriers.

History of GDSs

The GDS story begins in the middle of the twentieth century when the economic and technological boom promoted the rapid development of air travel. At that time, seats were booked over the phone or at the airline office, and staff used paper cards (or, at best, electromechanical devices) to keep track of reservations. Naturally, the airline industry searched for tech solutions to speed up the process and meet demand.

In 1961, Trans-Canada Airlines (now Air Canada) successfully tested ReserVec, a computerized reservation system developed with Ferranti Canada. In 1963, the airline switched entirely to ReserVec bookings. However, the system failed to take off; it quickly lost out to its competitor, fading into oblivion in the 1970s.

This competitor was SABRE (Semi-Automated Business Research Environment), the computer reservation system (CRS) developed by IBM and commissioned by American Airlines. The new instrument could process more than 7,000 reservations per hour with virtually no errors and immediately gave the airline a significant advantage in the market.

Other players rushed to catch up, and by the early 1970s, almost all major American and some European carriers had implemented their own reservation systems. They were based on the IBM technology created as an alternative to SABRE since it was quite costly to build a CRS from scratch.

“S” as “Semi” in the SABRE name meant the automation wasn’t full: Human operators in the airline had to take calls from travel agencies and input all the data into computer terminals. Over time, airlines provided travel agents with terminals giving direct access to their CRSs to free up airline manpower.

The Airline Deregulation Act, which passed in 1978, greatly impacted the industry. Let us name just a few of the changes introduced by this law. Previous tariff restrictions were removed, and carriers began to set prices without regard to regulatory authorities. The requirements for establishing new airlines were relaxed. The ban preventing international airline companies from engaging in domestic transportation was lifted.

As a result, many new players entered the market, and the industry pioneers took advantage of the situation: They started commission-based hosting the inventory of other carriers on their CRSs. This benefited both parties—newcomers didn’t have to buy expensive software products, and CRS owners had a new source of income.

However, the honeymoon was short-lived. Airlines that owned terminals ranked their flights higher than those of the competitive carriers. This practice raised antitrust concerns and highlighted the need for unbiased service. To prevent possible government intervention, United Airlines and American Airlines spun off their reservation systems—Apollo and Sabre, respectively—transforming them into independent entities.

This is how the concept of a unified platform was born, allowing the booking of flights from multiple airlines through one terminal. At the same time, a new term, “global distribution system,” emerged. Gradually, the GDSs started to support hotel room distribution, cruises, train travel, airport transfers, and car rentals.

At the beginning of the new millennium, the international market leaders were clearly defined:

- Sabre, which, as mentioned, was created by American Airlines in 1964 and became an independent company in 2000;

- Amadeus, founded in 1987 by Air France, Iberia, Lufthansa, and SAS; and

- Galileo, launched in the same 1987 by British Airways, KLM, Alitalia, Swissair, Austrian, Olympic, Sabena, Air Portugal, and Aer Lingus. In 1992, it was merged with Apollo GDS, created by United Airlines. Subsequently, Travelport took over Galileo.

Today, the same three global distribution systems—Sabre, Amadeus, and Travelport—lead the way in airline content distribution, providing unrivaled coverage in the market.

It’s worth noting that companies running GDSs grew into tech giants and now offer a vast array of IT solutions besides GDSs for airlines, airports, and resellers—from passenger service systems (PSSs) and dynamic pricing tools to travel and expense management software and payment platforms.

Watch our video to better understand how GDSs emerged, how they work, and how to handle them.

GDS vs CRS vs PSS: siblings, but not triplets

GDS and CRS are often confused. As mentioned, GDSs evolved from CRSs and initially had similar functions. But nowadays, they are entirely different tools.

A CRS (which could also be called a central or computerized reservation system) is a proprietary instrument that allows a company to manage its inventory and reservations. It stores reservation records, tickets issued, schedules, fares, and other flight-related information.

The CRS is usually integrated with the airline inventory and departure control systems, which together form the passenger service system.

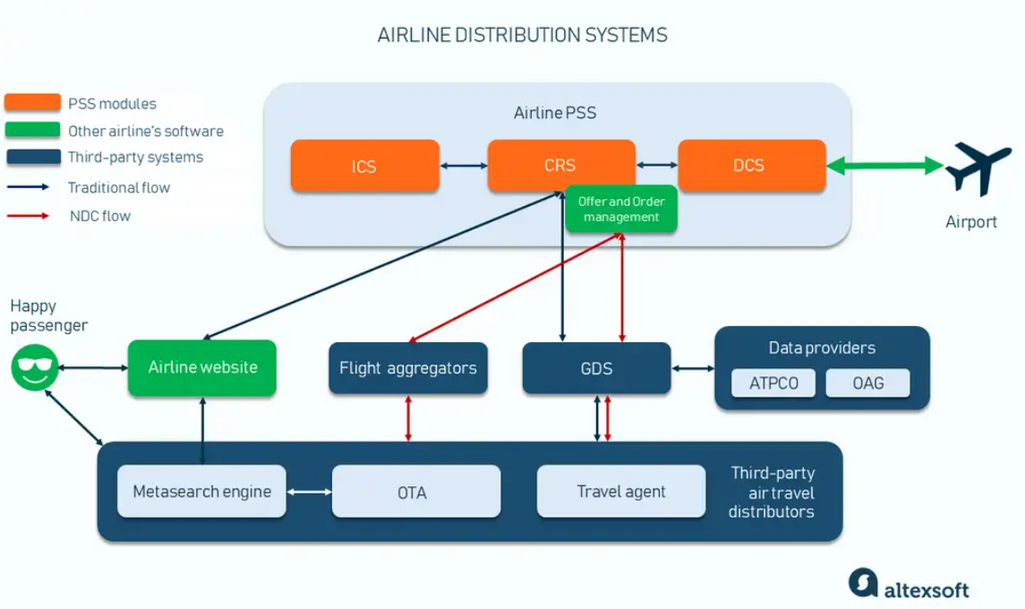

Airline distribution systems

A central reservation system was initially created for airlines, but hotels later adopted this solution. Read more about CRS in the hotel industry here.

GDSs, unlike CRSs, do not permanently store inventory data. They are multifunctional platforms designed to connect to multiple travel content providers and pull data requested by resellers.

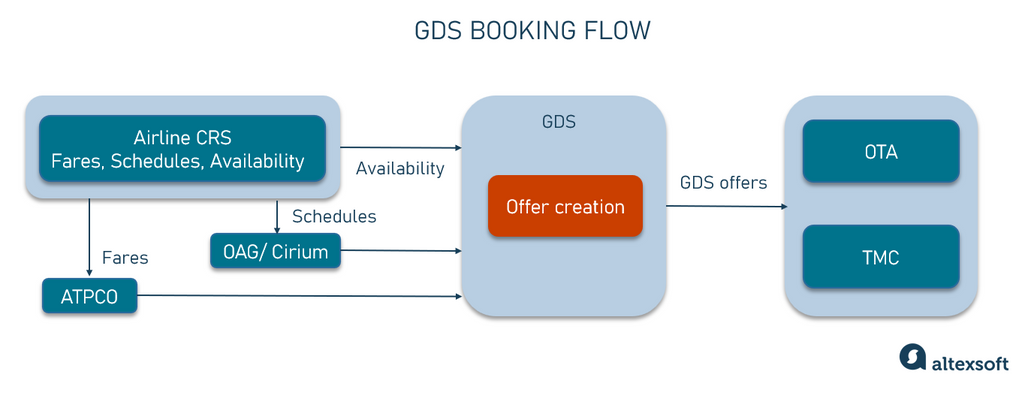

GDS booking flow

Let's take a look at what happens when a passenger uses an online booking platform— whether a leisure OTA or a corporate travel tool—to buy a flight.

GDS booking flow

Flight search. The GDS receives search details from the booking website via API and connects to different airlines' central reservation systems to get real-time seat availability. It also fetches prices from the Airline Tariff Publishing Company (ATPCO), the primary global source for fare information, and schedules from Cirium or OAG, the world’s largest repositories of flight scheduling data.

Offer generation. The GDS combines availability, price, and schedule data fragments into offers and sends them to the online platform.

Booking creation. After a traveler chooses the offer and enters personal info, including the form of payment, the website sends booking details to the GDS. The latter checks if the offer is still valid and requests the booking be created in the carrier's CRS.

Booking confirmation. The CRS generates a passenger name record (PNR) containing personal and travel itinerary details. Each record has a unique code called a booking reference. The GDS retrieves this code and passes it to the website, which then emails it to the passenger. The PNR number doubles as a booking confirmation and allows the traveler to manage their reservation—make changes or cancel the flight.

Ticket issuance. While booking confirmation happens almost immediately, it takes time to verify the payment and finalize the purchase. Only after the payment is approved does the airline provide the GDS with ticketing details to be forwarded to the agency that issues a ticket on behalf of a carrier.

Post-booking servicing. The GDS facilitates post-booking communication between airlines and agencies, be it rescheduling, canceling, or requesting for a refund.

To learn more about the flight booking process read our dedicated article.

Airline-GDS relationships, fees, and tech connection

GDSs have historically offered the most extensive coverage of the airfare market, a position they still hold. Companies operating GDSs also provide a wide range of tech products for airlines, including PSSs, for example, SabreSonic and Altéa by Amadeus. While some carriers have developed custom-built reservation systems, the vast majority rely on off-the-shelf solutions hosted and maintained by global distribution platforms.

So, are GDSs and airlines the perfect union? "They say all marriages are made in heaven, but so are thunder and lightning," opined the Clint Eastwood character in The Bridges of Madison County. This sentiment aptly describes the relationship between airlines and GDSs.

For over a decade, big carriers have been engaged in a tug-of-war with global distribution platforms. Since GDSs were airlines' main gateways to flight distribution, carriers have become highly dependent on them, while global distribution systems could dictate fees and delay tech innovations. Unfavorable terms caused growing frustration among carriers. Here are just a few examples of the conflicts generated by this discontent.

In 2011, US Airways (later merged with American Airlines) sued Sabre: The carrier accused the GDS of anti-competitive practices and charging excessive fees. After 11 years, a jury determined that Sabre engaged in unlawful practices but concluded that the contract between US Airways and Sabre did not restrict trade as the airline had claimed. American Airlines was awarded only $1 in damages, but after further claims, Sabre was obliged to pay $139 million in legal fees.

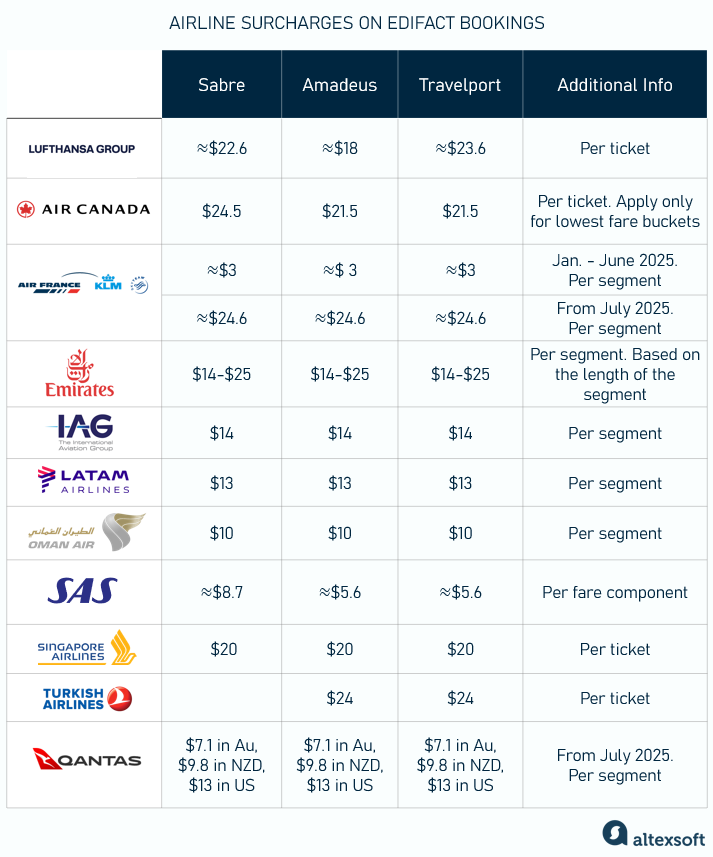

In 2015, Lufthansa Group was the first to announce a surcharge on bookings via global distribution systems, aiming to recover millions in annual costs and redirect its commercial strategy. Travel agents threatened boycotts, and GDS providers opposed the move, warning it could deter consumers. However, Lufthansa did not change its mind; its example was soon followed by other major players, introducing surcharges on ticket purchases through GDS.

In 2024, Turkish Airlines and U.S. low-cost carrier Frontier Airlines ended their agreements with Sabre (but stayed on Amadeus and Travelport). The airlines are simultaneously fighting and making peace with GDSs, leaving one and going to the other. But what is the main reason for all this turmoil?

Why are airlines unhappy with GDSs?

A GDS is a powerful distribution system solely designed for global use. It is fast, provides huge coverage, and allows travel agents to freely combine flights from different airlines. Hotels, for example, don`t have their own version of a GDS, and the hospitality sector can only envy what the airline industry has.

However, there are several reasons why major airlines are trying to minimize cooperation with GDSs, instead encouraging direct sales on their own websites or establishing a direct relationship with resellers.

EDIFACT-based infrastructure is outdated and rigid. A data exchange standard, EDIFACT (Electronic Data Interchange for Administration, Commerce, and Transport), was adopted in the 1980s. It’s highly structured, compact, and perfectly suitable for transmitting basic flight information such as schedule, tariffs, and seat availability. But EDIFACT can’t transmit rich content (text descriptions, pictures, videos) and, therefore, doesn’t meet the requirements of the modern eCommerce world where customers expect the comfort of a fully immersive digital marketplace.

Another issue is that the protocol (and, to be fair, the airline's underlying infrastructure, too) can’t quickly adapt to changes, which means it doesn’t allow for granular or continuous pricing and hinders introducing products beyond seats and basic ancillaries. Since an airline's margin from transporting passengers between two points is very low, carriers make most of their revenue on extra services, such as seat upgrades, additional baggage, priority boarding, or in-flight meals. EDIFACT supports only limited ancillary data; adding new features is complex and would take ages.

Airlines have no control over offers and no access to customer data during booking. In the GDS-centric ecosystem, a GDS, not an airline, creates an offer. The carrier can't create bundles, personalize its product based on a traveler profile, tailor prices on the go, etc. The presence of other data middlemen—ATPCO, OAG, and Cirium—also contributes to an airline's inability to control its products and build offers on the go.

We have fares that have to be filed and can be published an hour later. We have schedules that are separated from that. And these fares, by the way, must be distributed to third-party distribution companies, who then need time to process them. You hear how antiquated this is and how far from real time…

High fees. Under the standard commercial model, the GDS charges airlines a flat fee for each segment booked through their system, an average of $4-6 per booking segment or $16 per ticket (approx. 2.5 segments). Airlines are also charged for every interaction with the system: ticketing, refunds, and any other executed commands. Altogether, GDS fees can account for up to 25 percent of ticket prices.

Anti-competitive practices. For instance, the platform ranks airlines with CRSs hosted on it higher than the other airlines.

To address some of these issues, the International Air Transport Association (IATA) launched the new data transmission standard, NDC, in 2012.

NDC: transforming airline distribution standards

The New Distribution Capability initiative aims to modernize airline merchandising. It relies on an XML-based data exchange that accommodates multimedia content and allows for adding new data on the fly. NDC also introduced offer and order booking flow and messaging standards that pass content control back to the carriers.

In the NDC world, airlines build offers for indirect channels the same way they do it for their own website and communicate with third parties via NDC-enabled APIs.

In simple terms, NDC is the ability to control the way airlines’ content is distributed. NDC represents a paradigm shift by offering more opportunities and flexibility in distribution

You can read more about the benefits of NDC in our articles — NDC in Air Travel, NDC technologies for Airlines, or watch the video.

With NDC, indirect distribution is no longer GDS-centric. The initial idea was to completely exclude GDSs from the flight sales chain. It hasn’t happened so far and is unlikely to be realized in the foreseeable future—let’s see why.

Airlines' strategies to encourage NDC bookings

While the benefits are most obvious for airlines, it should not be forgotten that transitioning to new technology takes time and investment. According to IATA, only 77 airlines (approximately 20 percent of the IATA members) now provide NDC content, with leaders including American Airlines, Lufthansa Group, United Airlines, Qantas, Emirates, and Qatar Airways.

For resellers, the advantages of the new standard are far from obvious. First, a significant part of travel agencies' revenue comes from airline incentives (commissions and bonuses) for ticket sales. Second, NDC has yet to be perfected. It is often slower, less versatile and feature-rich than standard GDS flow. But, willing to eliminate GDS costs as quickly as possible, airlines implement a few strategies to motivate travel agencies to speed up the shift.

Impose surcharges called distribution cost charges (DCC) on traditional GDS EDIFACT bookings. For example, depending on the GDS, Lufthansa Group surcharges $18-24 for each booking. Turkish Airlines takes $24 no matter what GDS. Emirates surcharges $14-25, also GDS agnostic.

The GDS surcharges are supposed to motivate agencies to speed up the NDC transition

Restrict certain offers to direct or NDC channels. For example, Air France and KLM removed their lowest fares (short- and medium-haul “Light” fares, which include a minimum stay requirement) from EDIFACT channels in 2023 and have stuck to that decision ever since.

However, things didn't always work out the way the airlines expected. For example, also in 2023, American Airlines pulled 40 percent of its fares (the lowest ones) from GDS, but six months later, the company declared losses, which it attributed, among other things, to distribution strategy in corporate travel. Apparently, TMCs that traditionally book through GDS simply turned to the carrier's competitors for better offers. That’s when the carrier decided that a carrot was better than a stick and opted for bonuses to travel agencies.

Offer a reward for NDC booking. American Airlines has introduced a 10 percent commission on specific fare bundles booked through NDC channels, while Air Canada pays $2 per NDC booking via direct connection or selected intermediaries.

And what about the GDS? Contrary to everyone's expectations, they didn’t engage in confrontation but instead adapted quickly by integrating NDC alongside EDIFACT. Travelport now supports NDC content from 18 airlines, Sabre from 21, and Amadeus leads with 30. Still, it’s important to highlight that GDSs may not provide all NDC capabilities that an airline has implemented on its side.

It would be fair to say that the major airlines' revolt against the GDS oligopoly has not had the desired effect. However, a group of carriers has always gotten along just fine without an intermediary.

LCCs don’t use GDSs. Because they can

Low-cost carriers (LCCs) have avoided GDSs from the beginning to minimize costs and maintain low fares. By selling tickets directly through their websites, LCCs eliminate GDS fees, offer a wide range of ancillaries, enjoy upselling and cross-selling, and gain direct access to customer data.

Most low-cost carriers integrate with third-party platforms using APIs developed before the introduction of the NDC standard. In recent years, however, five of them have embraced NDC, including Pegasus (Turkey), Vueling (Spain), Jeju Air (South Korea), Scoot (Singapore), and Spirit Airlines (USA).

Why are low-cost carriers successful where legacy carriers struggle? It comes down to their target audience. LCCs focus on cost-conscious leisure travelers who book directly, while traditional airlines often serve corporate clients who rely heavily on GDSs for managing itineraries and bookings. On top of that, TMCs and corporations normally have agreements with carriers.

Another factor is that low-cost carriers often launch massive advertising campaigns when entering new markets, drawing in first-time customers who later search for their flights through metasearch engines.

That said, low-cost carriers sometimes leverage GDSs to reach corporate travelers. For instance, Canada’s Flair Airlines initially operated independently but later partnered with Amadeus.

Now that we've broken down the relationship between airlines and distribution platforms, let's consider the situation from another perspective.

GDS-agency relationships, fees, interfaces

For travel agencies, GDS provides an unrivaled variety of products, including flights from over 400 airlines and millions of hotel properties, car rental services, railway tickets, and more. To book air, the agency must acquire IATA certification. Smaller businesses that can’t afford the pricey accreditation typically get access to the GDS content using the credentials of larger players, such as airline consolidators and host travel agencies.

Interfaces: green screens, GUIs, APIs

There are three ways agencies can connect to GDSs: cryptic terminals (called green screens), graphical user interfaces (GUIs), and APIs.

Green screen is the oldest text-based interface where agents input commands in EDIFACT format using a keyboard. Many experienced agents claim to be faster with a green screen because there’s no need to take their fingers off the keyboard to use a mouse. At the same time, the terminal is rugged for new agents to master and lacks modern features like content aggregation. This interface is obsolete, and although there are still many green screen warriors in the professional environment, it will inevitably become a thing of the past.

Graphical user interfaces include agent desktops or mobile apps. All GDS giants provide modern GUIs—Sabre Red 360, Amadeus Selling Platform Connect, and Travelport+—that consolidate airline content in one place, presenting all types of offers (EDIFACT, LCC, and NDC) in a convenient, standardized format. Graphical user interfaces greatly simplify the flight booking process—yet, for some operations, agents still need to switch to the EDIFACT screen. That’s why, to use a GDS, a travel agent must complete a special training course.

GDS APIs. OTAs, online booking tools, and other web-enabled resellers integrate GDS content and features with APIs. For more information, read articles based on our hands-on experience integrating Sabre APIs and Amadeus APIs.

To learn more about how to integrate airline content, read our comprehensive articles about travel and booking APIs and airline flight booking APIs.

Why do travel agencies stick to GDSs?

The essential reason OTAs and TMCs stick to global distribution systems is money. First, shifting to new technology will bring a lot of trouble and expense, while there are no clear benefits for agencies. Secondly, GDSs pay agencies incentives, which are part of the fees received from airlines. Most airlines have yet to offer an adequate replacement for this incentive system.

Travel management companies rely heavily on GDSs because they provide back-office systems to manage key tasks like ticketing, invoicing, accounting, and reporting. Transitioning away from GDSs would require an investment in developing or buying alternative tools.

This situation is similar to one faced by airlines that rely on global distribution platforms to host their CRSs. It's no wonder TMCs have little sympathy for airlines' struggles with the distribution giants. “The biggest issue is simply infrastructure. TMCs and accounting systems are built around EDIFACT,” says Russel Carstensen, founder and CEO at Aeronology, a full-service travel point of sale that established NDC connections with all major airlines. “But that is changing. Smart back office and middle office companies are moving to API-driven applications.”

One more reason why large agencies are in no hurry to transition is that they see GDSs adapting to new technology. There’s good reason to believe that, over time, the whole ecosystem will switch entirely to the NDC standard, and then the agencies will reap the benefits without making any drastic changes.

So, what is the future of GDSs?

Airline distribution is undergoing a—very slow but unstoppable—transformation as digital channels take center stage. The traditional global distribution systems that once ruled the industry can no longer fully meet the expectations of airlines seeking more flexibility and cost-efficiency.

Large carriers fight to reduce dependence on GDSs. In 2023, an impressive 61 percent of passengers worldwide booked directly with airlines. And NDC, albeit slower than expected, is changing the landscape.

However, GDSs are unlikely to disappear, еven if the glow of this cornerstone of the travel industry has faded a bit. They will continue to evolve and expand their offerings, while airlines will keep investing in their digital channels. Let the competition bring out the best in products, right?

Olga is a tech journalist at AltexSoft, specializing in travel technologies. With over 25 years of experience in journalism, she began her career writing travel articles for glossy magazines before advancing to editor-in-chief of a specialized media outlet focused on science and travel. Her diverse background also includes roles as a QA specialist and tech writer.

Want to write an article for our blog? Read our requirements and guidelines to become a contributor.