Overbooking has been a widespread practice in the passenger aviation industry since the 1950s. Though initially caused by human mistakes, it soon became a common solution to the “no-show” problem – despite the related controversies.

Understandably, by overselling tickets, carriers aim to increase occupancy and prevent revenue losses – but is this strategy really effective? And is it worth bumped-passenger frustration? Let’s take a deeper look at how overbooking works.

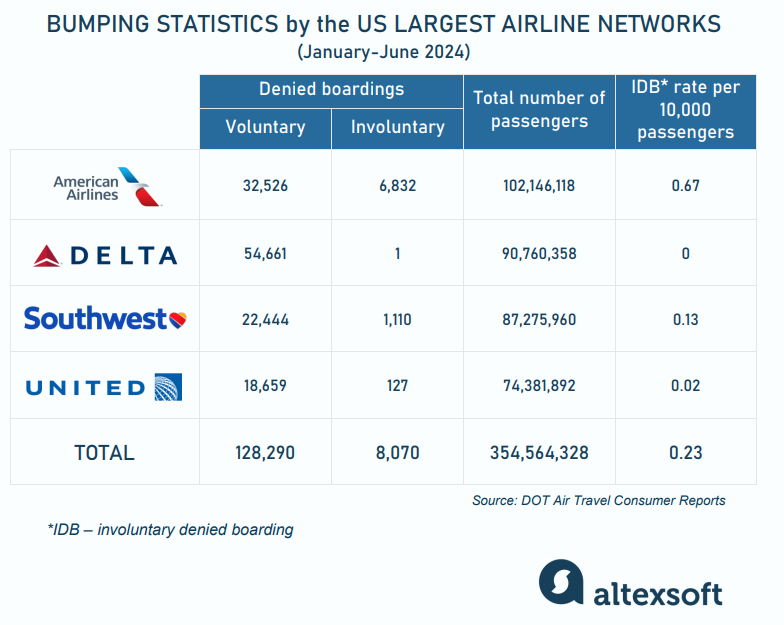

Bumping statistics of the biggest US airlines for January to June 2024. Source: DOT Air Travel Consumer Reports

What is overbooking?

Airline overbooking occurs when an airline sells more tickets for a flight than there are available seats on a plane. This ensures that flights operate at maximum capacity and minimizes losses from empty seats. Basically, that’s how carriers compensate for inevitable no-shows and last-minute cancelations.

The average no-show rate is alleged to range from 5 to 15 percent, depending on the season (say, before Christmas, people are less likely to miss their flight than on any given Tuesday), route, airline, and so on. The reasons travelers don’t show up vary greatly. The most common ones are

- changes due to unforeseen circumstances,

- heavy traffic on the way to the airport,

- long security procedures at the airport,

- missed connections, and

- skiplagging (getting off at the transition point of the connecting flight instead of proceeding to the final destination).

If a passenger doesn’t show up for the flight without informing the airline, they typically don’t get their money back, so carriers suffer minimal losses in that case. However, if a traveler cancels their booking last minute, the odds of reselling the ticket are miserably low. So the airline risks having that seat empty – and losing money.

To avoid those losses, carriers try to forecast how many people don’t make it to the boarding gate and sell a few extra tickets to fill the plane. But what if the prediction isn’t accurate enough and everyone shows up? In this case, passengers are being bumped – or denied boarding the plane, frustrating as it may be.

Voluntary bumping

When more ticket holders show up for the flight than expected, airlines typically first try to find volunteers. The staff suggests travelers waiting at the gate give up their seats in exchange for negotiated compensation for inconvenience. This is known as voluntary bumping.

As a rule, the airline would offer the volunteers to take a seat on a later flight or some other form of alternative travel arrangements. Some other perks that can be included in compensation are

- vouchers for flights or other travel products (meals, transportation, hotel stays, etc.),

- cash refunds,

- future travel upgrades, etc.

Needless to say, voluntary bumping is the preferred solution for airlines because it minimizes passenger dissatisfaction and allows them to avoid bad publicity. Some airlines even offer to add a traveler to the volunteer list during check-in, which then makes things even simpler.

But sometimes there's a lot less congeniality...

Involuntary denied boarding (involuntary bumping)

If not enough passengers agree to give up their seats, the airline may have to resort to involuntary bumping. This means the gate agents themselves select who will not be boarding, typically based on criteria like

- the fare paid (often, the lowest fare tickets are at bigger risk of being bumped),

- check-in time (the latest check-ins are often the first to be denied boarding), or

- frequent flyer status (the highest tiers are rarely being bumped).

Involuntary bumping be like. Source: Lauren Mathews on X

Of course, airlines try to add a spoonful of sugar to make the medicine go down (i.e., avoid bad publicity) and compensate for the trouble. It usually involves reserving a seat on an alternative flight and offering additional bonuses.

In any case, involuntarily bumped passengers are legally entitled to compensation. Its amount is often 200 to 400 percent of the ticket price, but it can be different depending on the airline, route, time of delay, and other factors (we’ll discuss the legal requirements further).

After United Airlines infamously and forcibly dragged a passenger off a plane in 2017, many carriers have reviewed their policies and raised the compensation to as much as $10,000 per seat.

But despite the seemingly substantial losses, both financial and reputational, airlines still have overbooking as a common practice. But why?

Why do airlines overbook?

The average net profit margin in commercial aviation is around 2.6 percent as per IATA. Flights are expensive to operate, and every empty seat is a hard hit on the bottom line. To address the risk of operating at less than full capacity and minimize revenue leakage, airlines have several options.

One is raising the ticket price to pass the costs of lost seats to travelers. But since aviation is a crowded industry, charging more for seats isn’t really a viable strategy. Carriers heavily invest in dynamic pricing technologies to ensure they offer optimal, competitive fares.

You can also get more in-depth information on the topic from our posts about the dynamic pricing strategy for airlines, AI revenue management in aviation, and flight price predictor development.

Another option is charging fines for no-shows. At some point, airlines tried to implement this practice, but bad publicity and social resistance made most of them abandon it. So today, depending on the airline, a no-show fee may be the whole ticket price or a portion of it that’s not refundable.

Meanwhile, overselling is a calculated risk that aims to fill more seats and generate more revenue – despite occasional compensations. This takes us back to our initial question: Does this strategy actually work? Let’s get more specific and talk some numbers.

How effective is overbooking?

For example, let’s take an average one-way US domestic flight. Let’s say airline X flies a Boeing 737-800 carrying 160 passengers, which may generate around $30,000 in ticket sales (given that the average airfare for a roundtrip in the US in 2024 is around $388).

If 10 percent of those passengers cancel right before takeoff, airline X would lose $3,000 per flight (in case travelers apply for a refund). However, by overbooking by 10 percent (or 16 additional tickets), the airline compensates for those potential no-shows and can fill all the seats, recapturing that $3,000.

If $3,000 in saved revenue doesn’t seem very impressive, scale it to the traffic numbers. Ryanair operates up to 3,600 flights per day, Delta flies 4,000, United does an average of 5,000 departures daily, and American Airlines offers 6,700! Over the course of hundreds of thousands of flights per year, airlines can increase revenue by tens of millions of dollars.

As for compensations, with an average IDB rate of 0.3 per 10,000 passengers, the cases of payouts to involuntarily bumped passengers are very rare and will only occur once in about every 200 flights. And the incentives to volunteering travelers are often non-cash, such as vouchers and future upgrades, so they don’t impact revenue that much.

So you can see that even though the risk of customer annoyance is high, the financial gains from overbooking outweigh the impact of negative PR. Well, money talks.

But when well-managed, with data-driven calculations and proper compensation policies in place, overbooking strikes a balance between profitability and customer satisfaction. So let’s take a look at the technologies that make all this work.

No-show prediction

Airlines are not simply overbooking flights by unrealistic numbers. They are booking on very specific proven data for that exact flight.

Carriers do their best to forecast the percentage of passengers who don’t use their tickets – as well as the optimal number of extra seats to sell. For example, if a flight has a 10 percent expected no-show rate, an airline may overbook by 5-10 percent, depending on its risk appetite. But how do they know it’s going to be 10 percent?

Today, advanced AI/ML-based revenue management technologies help predict a no-show rate for any given flight. For most accurate forecasts, massive amounts of varied data are factored in, including

- historical no-show rate for this route,

- foot traffic at the airport,

- road traffic and weather conditions,

- public holidays,

- big business or entertainment events,

- delay time of connecting flights,

- the cost of compensation, and much more.

Various ML algorithms are used to predict no-shows. For example, recent research evaluated several classes of algorithms, from random forests and decision trees to gradient boosting and neural networks.

Check out our full guide to machine learning to learn more about how they work.

Trained ML models help identify specific patterns in data, such as booking trends during various times of the year or in different economic conditions. They also define passenger segments based on past travel habits, loyalty program data, and booking preferences. For example, frequent business travelers may have lower no-show rates compared to leisure travelers.

To achieve optimal results and maximize profitability, revenue management systems balance the potential loss from no-shows with the expected compensation costs. Often, the simulation and scenario testing platforms are used to run and compare different overbooking strategies.

Summing up, airlines continuously analyze large amounts of data and dynamically adjust their overbooking strategies, selling more or fewer seats depending on the forecast. And it seems to work.

How often do passengers get bumped?

With technology enhancements of the last decades, the no-show prediction accuracy increased. As a result, the average denied boarding rate has been steadily decreasing over the years.

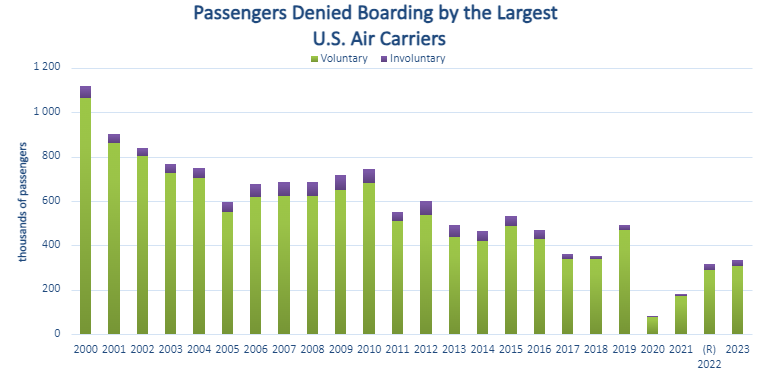

Denied passenger statistics in the US. Source: Bureau of Transportation Statistics

As you can see in the graph, there was a general decrease in the number of bumped passengers from 2000 to 2019 (despite the growth of overall flight traffic). In 2020, the pandemic halted air travel which steadily resumed in the following years. And even though today passenger air traffic has surpassed prepandemic levels, the number of bumped passengers remains lower than before.

As of writing this post, the involuntary denied boarding rate (IDB) fluctuates around 0.3 per 10,000 passengers – sometimes getting as low as 0.2 (Q4 2023) – according to the DOT’s Air Travel Consumer Reports.

Speaking of the DOT, it’s time to address the regulations that prescribe how airlines should behave in relation to no-shows.

Overbooking regulations

Regulations protect passengers and define their rights when it comes to overbooking. They mandate that airlines compensate bumped flyers and list minimum financial requirements for various cases – though, of course, carriers are free to increase the compensation amount or offer additional perks to resolve situations amicably.

There is no limit to the amount of money or vouchers that the airline may offer, and passengers are free to negotiate with the airline.

Also, while airlines are generally not allowed to remove passengers on the overbooked flight after they board the plane, the regulators specify that it can happen due to security reasons, health risks, or disruptive behavior.

At the same time, regulators explicitly prohibit discriminating against passengers and denying boarding to anyone based on race, gender, or any unreasonable prejudice.

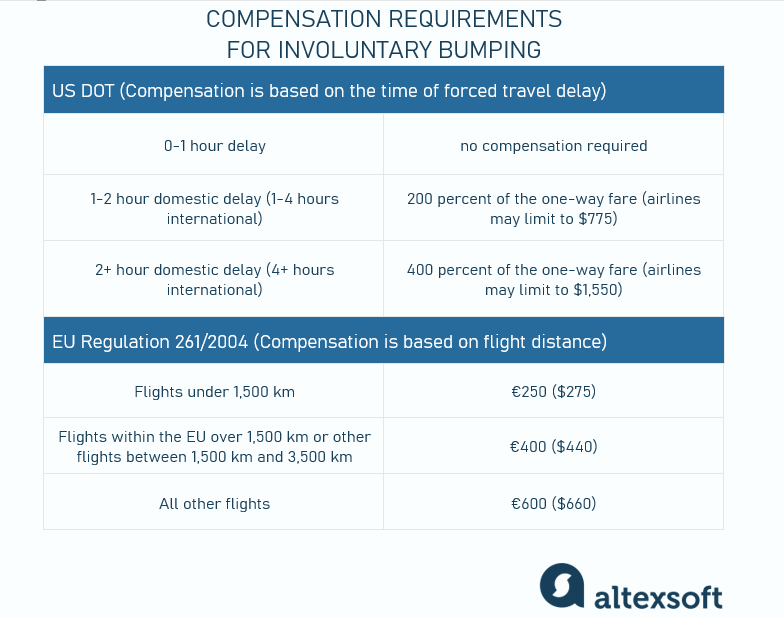

Compensation requirements

In the US, the Department of Transportation (DOT) regulations require the airlines to compensate involuntarily bumped passengers with amounts based on the time of forced travel delay:

- 0-1 hour delay – no compensation required;

- 1-2 hour domestic delay (1-4 hours international) – 200 percent of the one-way fare (airlines may limit to $775);

- 2+ hour domestic delay (4+ hours international) – 400 percent of the one-way fare (airlines may limit to $1,550).

In Europe, the EU Regulation 261/2004 sets the following compensation for denied boarding:

- flights under 1,500 km – €250 ($275);

- flights within the EU over 1,500 km or other flights between 1,500 km and 3,500 km – €400 ($440);

- all other flights – €600 ($660).

By now, we’ve mostly discussed the perspectives of airlines and regulators. But what do passengers think of overbooking practices?

The passenger perspective: Is bumping always bad?

While overbooking may sound like a risky practice to an ordinary person who may not have a deep understanding of the sector, it doesn't cause too many issues.

Well, from a traveler’s perspective, overbooking can be a bit of a mixed bag. On one hand, it definitely can be a pain in the neck, especially if someone gets bumped involuntarily. Missing a particular flight can lead to disrupting further plans, whether a person travels for business or leisure.

But it’s not always just inconvenience and frustration. For those with flexible schedules, it’s almost like hitting the jackpot. If a traveler is open to being bumped, there’s a chance of getting a handful of perks – think free travel vouchers, seat upgrades, or even some extra cash. Moreover, as we mentioned earlier, there are plenty of stories of people intentionally booking tickets on oversold flights and getting desirable compensation.

If we look even deeper into the issue, passengers also benefit from the overbooking practice because it helps airlines keep airfares low—though most travelers are probably unaware of it.

Besides, as IATA accurately noted, “For consumers, this practice is beneficial because it allows more consumers to fly at the time, date, and fare of their choosing. We have all experienced the frustration of our preferred flight being sold out. Imagine if that were a regular occurrence, only to find out that there were empty seats on the plane?”

IATA also points out the environmental benefits of operating fuller planes. If you want to learn more about how it works, read our posts about sustainability in travel and carbon offsetting in aviation or watch our video about green travel below.

What is green travel?

Real-life overbooking examples and strategies

Most airlines today oversell tickets to manage no-shows. Here’s a brief look at what some of the big guys are doing.

Delta. Delta has one of the lowest IDB rates in the industry. At the same time, it has the highest number of voluntary bumping cases, which means it prefers to resolve issues amicably. And indeed, it’s known for a few impressive payouts. For example, in 2022, Delta handed out $10,000 to several passengers as compensation for an oversold flight. In 2023, the carrier offered up to $4,000 to volunteers for giving up their seats.

United Airlines. After that well-publicized overbooking incident in 2017 we mentioned earlier, United implemented policies to increase the maximum compensation offered to bumped passengers to $10,000. This resulted in a significant decrease in the IDB rate in the following years. However, the carrier also had cases of paying out $10,000 for voluntary bumping – in travel vouchers though.

Frontier Airlines. The low-cost carrier has been notorious for bumping passengers. For years, it has been reporting the highest IDB rate that exceeds that of its full-service competitors by multiple times.

British Airways. BA is said to oversell about 500,000 seats per year, with 24,000 passengers bumped from their flights.

Ryanair. Some airlines such as Ryanair do not overbook flights as per their policy. However, they also include a clause that passengers can be denied boarding in rare circumstances, for example, when the seat is needed for a crew member or a Federal Air Marshall.

Maria is a curious researcher, passionate about discovering how technologies change the world. She started her career in logistics but has dedicated the last five years to exploring travel tech, large travel businesses, and product management best practices.

Want to write an article for our blog? Read our requirements and guidelines to become a contributor.