What kind of AI we’re talking about - Artificial General Intelligence (AGI)

“We just ended slavery not too long ago, and in some parts of the world it still exists, and yet our greatest ambition as a species is to create new slaves that we can completely dominate and manipulate as we please. AI research is a disgusting abomination and it should be completely banned across every corner of the Earth for moral reasons alone."

From the comments section of a popular tech magazine

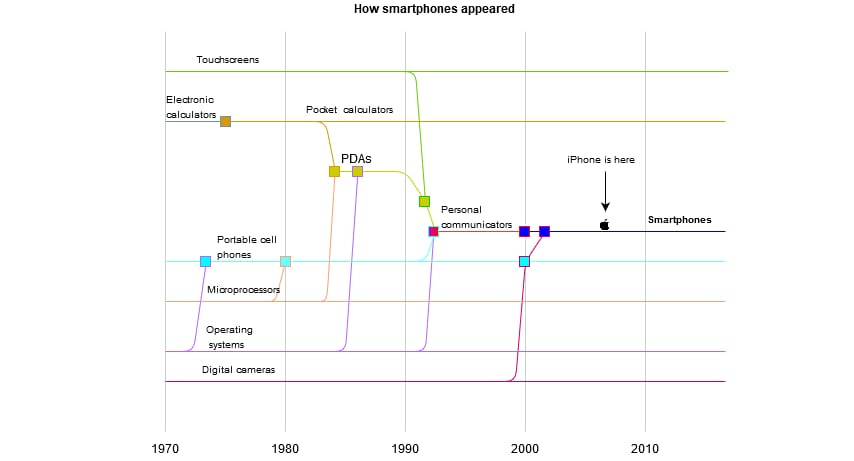

What kind of AI plants so much fear into people’s minds? The thing is, we already have a whole horde of algorithms that we refer to collectively as AI. AI is in video games that sometimes act like trained professionals and sometimes, well... don’t. Google, the search engine that became a verb, is AI. An unpredictable and annoying AI ranks posts in the Facebook newsfeed. AI is responsible for remarketing ads that haunt you everywhere across the web if you’ve ever considered buying something online. Even your weather app that recommended taking an umbrella is AI. These don’t look too dangerous, unless you let AI commandeer your life and take you on ride in the back seat of an autopilot-driven Tesla. Existing variations of AI are very narrow-minded and can only do the things that programmers tell them, either explicitly or through machine learning. Calculators are very good at multiplying or dividing large numbers, but that’s as far as they can get. That’s why we call this kind of AI artificial narrow intelligence (ANI). Ominous AI talks ranging from moderate wariness to outright panic relate to AGI (artificial general intelligence). And what kind of a beast is that? We simply don’t know because we haven’t yet seen one. It’s assumed that AGI will have the same cognitive abilities as humans do. In other words, it’s supposed to think and reason as we do or much better, given the advantage of computational power over human brain power. Here're some expectations for AGI that derive from common things that humans are good at:- Understand natural language and converse so that humans won’t tell the difference

- Represent knowledge

- Generalize objects

- Learn

- Solve puzzles

- Feel free to name some yourself. . .

- In 2014, “Eugene Goostman,” ostensibly a 13-year-old boy from Ukraine, won the Turing test. Or Eugene’s creators did. A program developed by Vladimir Veselov, a native of Russia currently living in the United States, and Ukrainian Eugene Demchenko, now living in Russia, bamboozled 33 percent of the judges into thinking that it was indeed a boy texting with them.

- And back in 2011, Watson, the intelligent IBM machine, became the champion of TV show Jeopardy!

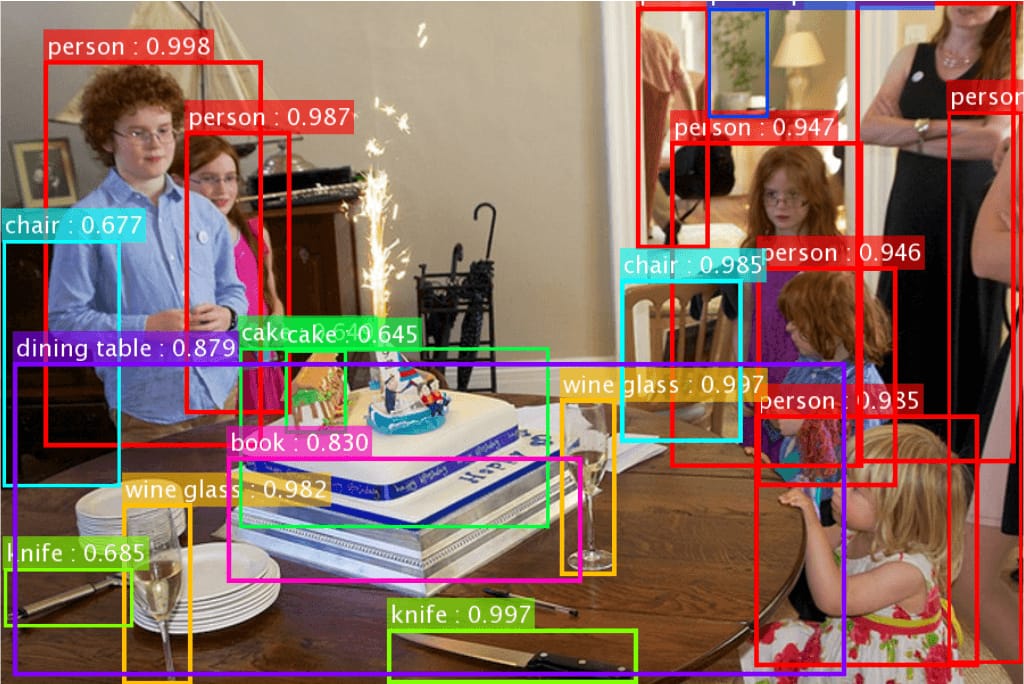

- To prove that algorithms can generalize and learn – at least to some extent – check the object recognition of images that Google, IBM, Cloudsight, and some other systems do.

- Even the most complicated puzzle in the world – like the game of Go (it brags about having more possible board combinations than there are atoms in the Universe) – was tackled by a computer. More specifically, the computer won the game against its human champion.

How we predict AGI

“One thing that we can be quite certain of is that any predictions we make today, for what the future will be like in 50 years, will be wrong.”

Elon Musk, WGS17 Session

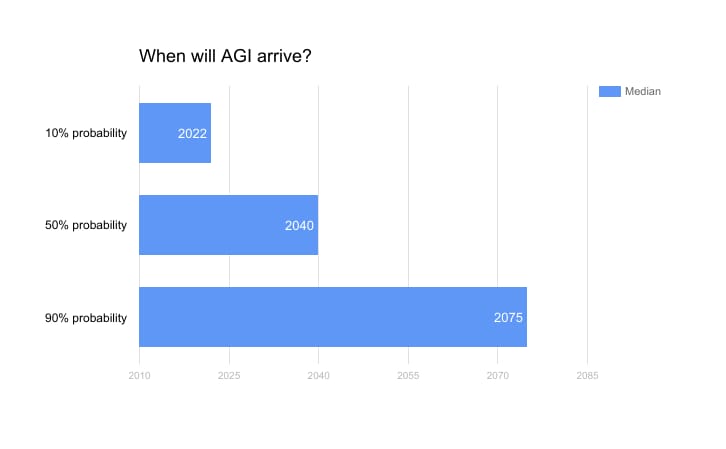

We all know that sci fi sucks at predicting the tech future. 2001: A Space Odyssey has impressively predicted the invention of some artifacts like tablet computers, but it obviously has failed at timing. Other examples are even worse. Nostromo, the spacecraft from the film Alien that travels long distances through space, has CRT monitors. Flying cars have been a great disappointment, the real flying cars, not those refrigerators with wheels and propellers from the Netherlands. And by the way, where are hoverboards? Well, for the sake of compelling drama, it’s okay that fi beats the crap out of sci. In real-world forecasts, we’re far more accurate, aren’t we? The fear of AGI becoming reality was widely propagated after Elon Musk and Stephen Hawking endorsed the thinking of Nick Bostrom, an Oxford philosopher. The warnings had been expressed before that, but Bostrom’s fears were planted in the fertile ground of public opinion, given the latest AI advancements. Bostrom surveyed top AI researchers asking when AGI is likely to arrive and whether this poses an existential threat to humanity. He even wrote a book about it. The main concern is whether we are ready to face a machine that can easily excel at human cognitive abilities, become super intelligent, and win the superiority cup on this planet. Returning to the previous concern – we don’t know what AGI means and whether we could even compare humans with this hypothetic machine. This doesn’t, however, stop scientists from making predictions. Bostrom’s research unites participants of AI-related conferences (PT-AI 2011 and AGI 2012), members of the Greek Association for Artificial Intelligence, and Top 100 authors in artificial intelligence by citation in all years. The survey asked experts by what year they see a 10% / 50% / 90% probability for AGI.

Source: Future Progress in Artificial Intelligence: A Survey of Expert Opinion

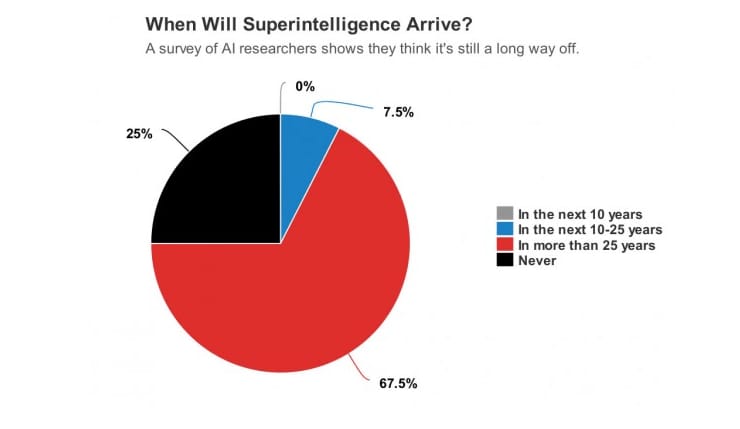

The experts suggest that by 2040 we have a 50 percent chance to actualize AGI. In the research, they call it HMLI (high-level machine intelligence), which “can carry out most human professions at least as well as a typical human.” And it’s very likely that in about 60 years machines will reach this level. To have a better idea of opinion distribution, it’s worth mentioning a survey of American Association for Artificial Intelligence members by Oren Etzioni, a professor of computer science and CEO of the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence. This one is more straightforward and simply asks when superintelligence will arrive. The concept of superintelligence implies that AGI will exceed human cognitive capabilities soon after being invented. And yet, it’s no less fuzzy a concept than AGI.

Source: MIT Technology Review

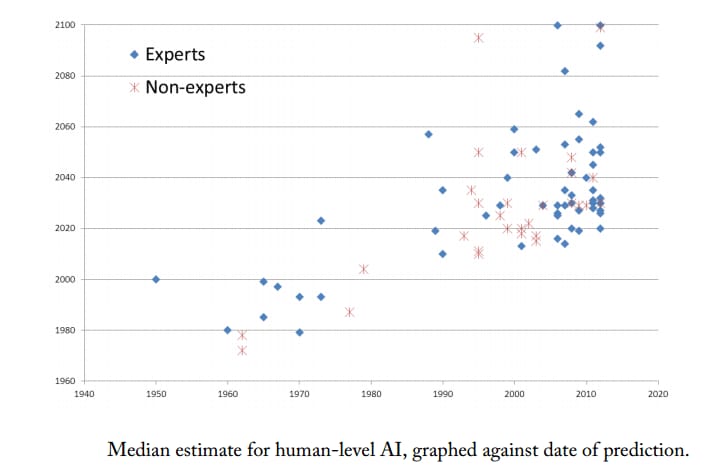

Dr. Etzioni seems comfortable claiming that 25 years into the future is beyond the foreseeable horizon. But for many of us who plan to make it through another quarter of a century, the prediction is a bit disturbing. We have a significant need to trust these expert opinions. Who else can we trust? These people are talking about the things they excel in, right? It appears different. In a particularly interesting paper, “How We’re Predicting AI — or Failing To” from the Machine Intelligence Research Institute, the authors explored 95 AGI expert predictions, spanning from the 1950s to 2012, and compared them to forecasts made by non-experts, writers, journalists, etc. And here’s what they found.

Source: How We’re Predicting AI—or Failing To

Not only do the predictions of experts contradict each other, many forecasts differing by 50 years, non-expert predictions aren’t outlying! In fact, they are relatively similar to each other: “There does not seem to be any visible difference between expert and non-expert performance either, suggesting that the same types of reasoning may be used in both situations, thus negating the point of expertise.” - authors of the paper say. It’s up to everybody to decide who to trust, but maybe there’s an immanent reason that prevents experts from making unambiguous estimations.Evolution is a bad metaphor when it comes to tech

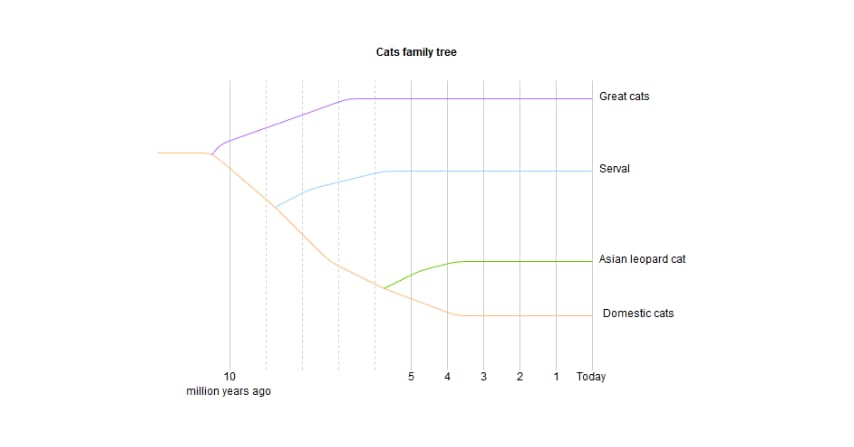

The evolution of a species is often exploited to metaphorically describe how technologies develop. And its main point – survival of the fittest – stands as the analogy with market selection. It rewards most adapted products and penalizes the rest. Although intelligent design seems more purposeful than random mutation, it impacts the velocity of change but doesn’t ruin the comparison itself. Every invention is constrained by cultural, psychological, economic, and ultimately technological circumstances. They act as a selective environment. This sort of reasoning makes us conceive of the upgrade from ANI to AGI as a linear and inevitable result of technological evolution. It will take some trial and error, but eventually we’ll be there. However, not all characteristics are similar. Even more than that, there’s one little difference that messes up all predictions. Let’s talk about cats. First of all, they are cute, but also cats are a good way to showcase how the evolution of species is different from technology development. Here’s a little insight into the evolutionary tree.

What are the enablers?

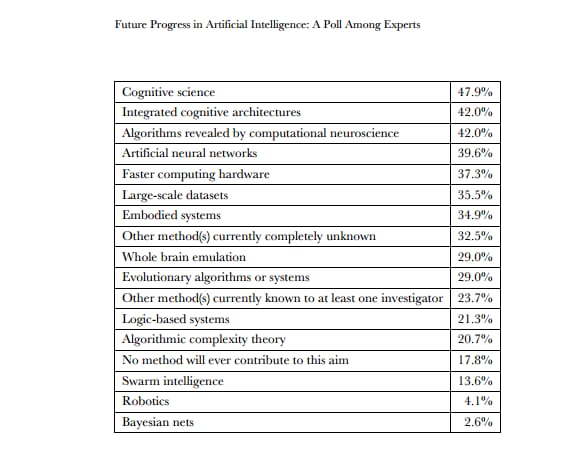

The scientists surveyed for Bostrom’s paper named multiple research approaches that might contribute the most to AGI invention. More than one selection was possible.

Source: Future Progress in Artificial Intelligence: A Survey of Expert Opinion

As the authors note, there’s neither significant difference between groups, nor are there relevant correlations between the answers given and the accompanying time predictions that we’ve mentioned before. So, it’s more guesswork here than substantial assessment. Of interest though is that many approaches revolve around deeper understanding of human cognitive specifics and building machine learning algorithms based on them. So, let’s talk about these.Deep neural networks

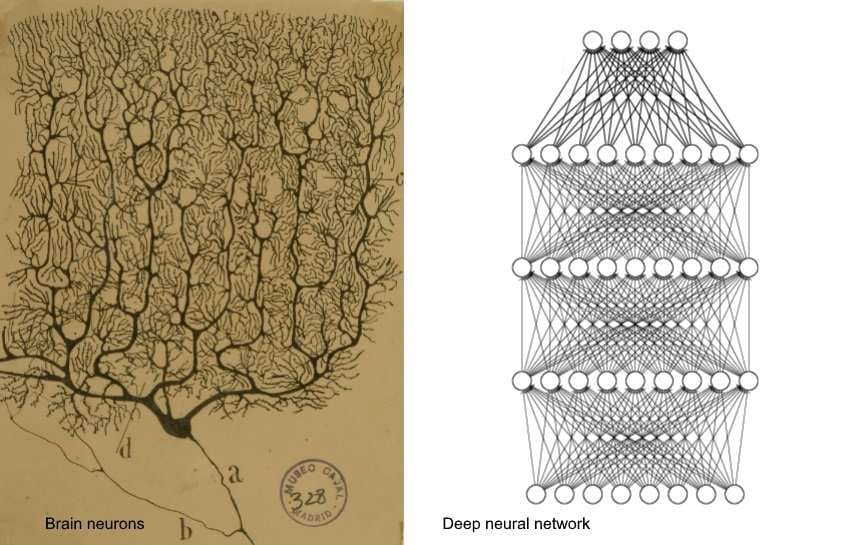

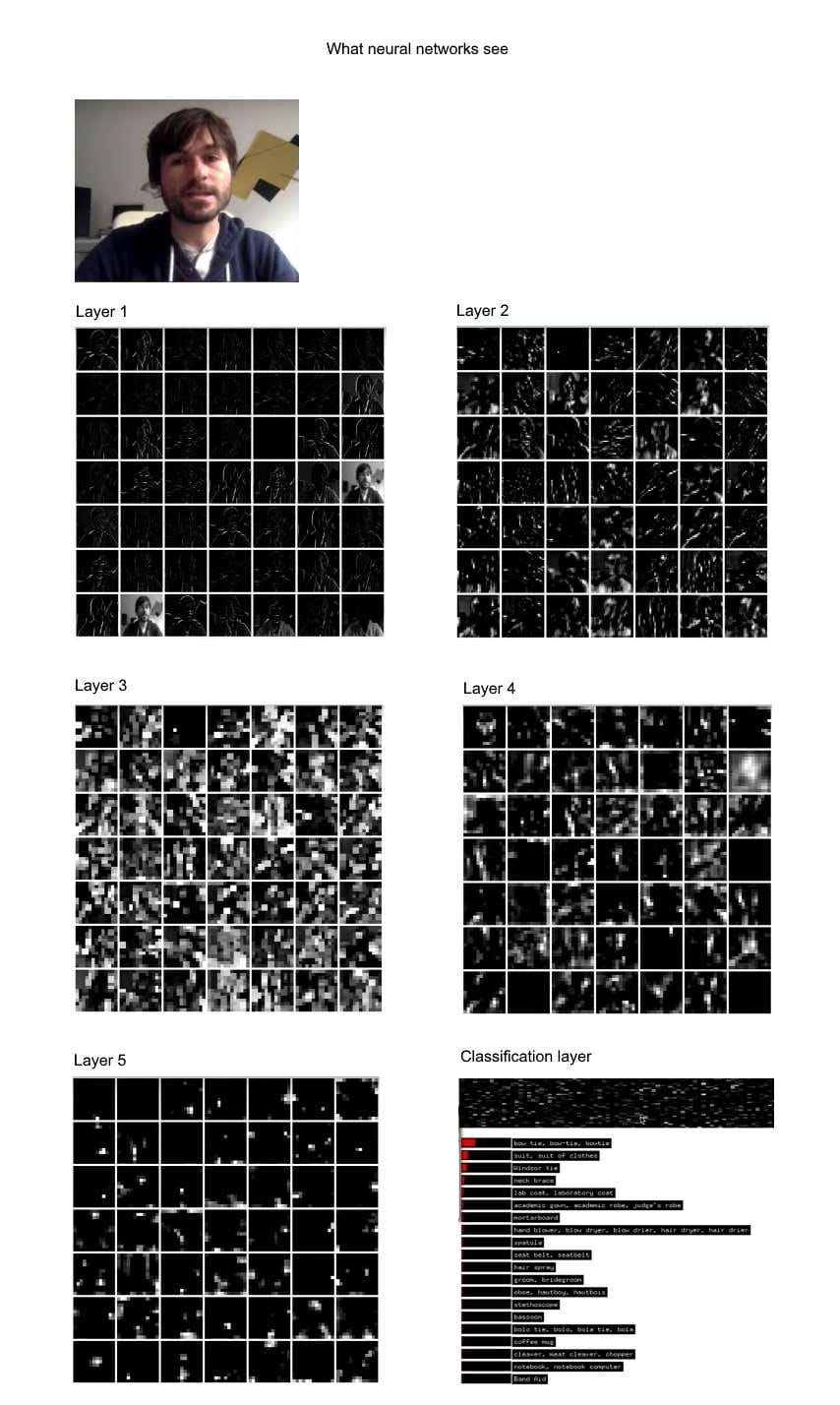

Perhaps the most hyped branch of machine learning is deep learning. It was used in AlphaGo, IBM Watson, and basically in most systems that make headlines in tech magazines today. The main idea behind deep learning is to build something like the brain, specifically to imitate the ways organic neurons work. It sounds promising, but in reality, we used brain-cell architecture as a source of inspiration rather than just copying them, let alone making them as effective.

Can we scale deep neural networks?

That’s a big problem. Scientists can’t just stack up layers until they get something intelligent. Constructing these layers and defining how they should interact with each other is an extraordinary task, which becomes even more challenging as we keep adding layers to the network. Another part of the problem of going “deeper” is that the signal that travels through these layers tends to fade as the number of layers grows. A record-breaker here is the research team from Microsoft that managed to build a deep residual network consisting of 152 layers. The trick is to skip some layers if they aren’t needed and use them when they are. This helps preserve signal and reach a notable result of high object classification accuracy. Also, researchers applied a semi-automated system that helped them find the working arrangements for the network, instead of manually constructing it.

Source: Deep Residual Networks Deep Learning Gets Way Deeper

But even considering the ingenious ways of scaling deep neural networks, we have a pretty narrow span of tasks in which to employ them. Basically, they fit well into three main categories: operations with images, speech, and text. No matter how deep neural networks get, they are still very task-specific. “When you look at something like AlphaGo, it's often portrayed as a big success for deep learning, but it's actually a combination of ideas from several different areas of AI and machine learning: deep learning, reinforcement learning, self-play, Monte Carlo tree search, etc.” - says Pedro Domingos, a professor of computer science from the University of Wisconsin. Deep learning is a powerful enabler but it’s definitely not the only one that may contribute to AGI.Brain reverse engineering

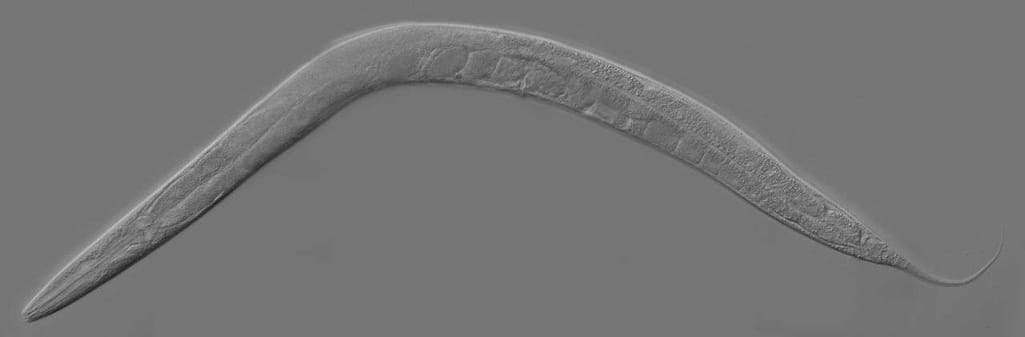

Why don’t we approach the problem from the other side? Instead of scaling from simple analogies of brain operations, we can take a brain and try to imitate its structure altogether. Connectome is a relatively new concept that implies mapping the whole brain and all neuron connections in it. The approach seems reasonably straightforward. Scientists take some organic brain, slice it to thin layers, and using an electronic microscope try to make a virtual brain model that simulates the real activity. Today we can simulate genuinely complex systems with many variables like hurricanes, for example. If we apply supercomputers able to process big data, this seems feasible. But let’s come back down to Earth. So far, connectome studies have achieved definite results with only one creature. This guy.

Source: Wikipedia

This is Caenorhabditis elegans, a little worm whose brain was sliced and mapped back in 1986. About 20 years later, Dmitri Chklovskii of Janelia Farm Research Campus and his collaborators released the final version of the map. C.elegans has only 302 neurons with 7000 connections, synapses, between them, not very impressive compared to human brains, since we have 86 billion neurons and 100 trillion synapses. So, one cubic millimeter of a brain mapped with sufficiently high resolution requires about two million gigabytes of data. But the sad part of it isn’t only the amount of computing storage and power to emulate activity. We have another problem – interpretability. Currently, scientists can understand how C.elegans’ brain responds to temperature, some chemicals, mechanical stimuli, and a number of other qualities. The research took decades and it seems now that we have underestimated the complexity of the brain. When you start analyzing behaviors that are more complex than reflexes, the interpretability of organic neural networks becomes an extraordinary barrier. Not only does the strength of connections between neurons vary, but also, they dynamically change each day. We don’t know exactly how neuromodulators would alter the simulation, how feedback loops that wire neurons together work, and so on. There are also several research groups that try to simulate little chunks of human brain, specifically to recreate visual recognition. But still, brain reverse engineering hasn’t achieved much on the way to building actual intelligence. Today scientists struggle to understand basic processes at the micro level.